The 1981 UK riots were spurred by police handling into the investigation of the New Cross fire where 13 young black people lost their lives as well as serious social and economic problems affecting Britain’s inner cities.

Following the New Cross Fire and Black People’s Day of Action march, and after several years of blatant provocation by the British State and the far right, Black youth finally reached a boiling point. Much like the race riots of 1919, the 1981 riots were widespread. Starting in Brixton in south London, the summer of 1981 saw riots break out in Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham and Leeds.

The most serious riots were the Brixton riots in London, the Toxteth riots in Liverpool, the Moss Side riots in Manchester, the Handsworth riots in Birmingham and the Chapeltown riots in Leeds. There were also a series of less serious riots in other towns and cities.

The Brixton riots

The Brixton riots were not planned. Many people were shocked by the unexpected turn of events. On the surface, it seemed that black people had blended well into the fabric of UK society. Many were second generation, born to parents known as the Windrush Generation, who had come to Britain from the Caribbean in the late 1940s and 1950s to help “the motherland” with post-war rebuilding.

But below the surface tensions had been building up due to serious social and economic problems affecting Britain’s inner cities. There was a disproportionately high level of unemployment among young black men. In Brixton, this was as high as 50%.

Added to that was what many believed to be targeted harassment of black people by the police. Brixton was a tinder box waiting to explode and on the night of 10 April, it finally did.

The local community was provoked by “Operation Swamp” also known as the Sus law, a system of policing that the police brought in five days earlier. The Sus Law was based on the 1824 Vagrancy Act. This meant that a police officer could stop, search and arrest people on suspicion that they might commit a crime in the future. Plain clothes police flooded the streets of Brixton using the powers of stop and search to arrest anyone who they believed to be loitering with intent to commit a crime. In five days almost 1000 people had been stopped and tensions on the Brixton streets reached breaking point.

On the night of Friday, 10 April two police officers were attempting to help a black youth who was bleeding from a suspected stab wound when they were approached by a hostile crowd. The crowd believed the man was being harassed by the police. The crowd of young people grew larger and more hostile, throwing bottles through police vehicles’ windscreens. The incident seemingly ended when police reinforcements arrived.

The build-up of police patrols in the area continued throughout the night and by Saturday afternoon, there were no less the 84 police officers patrolling the streets of Brixton, as well as three police vans driving round the area. The heavy police presence heightened tensions in the area.

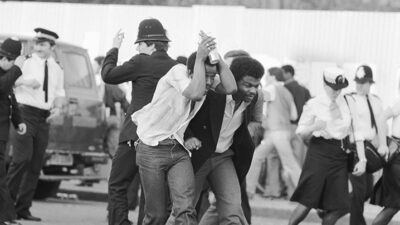

On Saturday afternoon, two police officers searched and arrested a young Black taxi driver. Missiles were thrown at the police van as it left. This led to more police reinforcements and resulted in the worst day of the rioting. The rioters were mostly young black men but they were now joined by young whites. Looting began, police vans were overturned and bricks, bottles, and petrol bombs were thrown, setting fire to both police and private cars.

For three days, rioters fought with police, attacked buildings and set fire to cars.

What happened after the Brixton riots?

After the riots, there was a public investigation led by Lord Scarman, into why the riots happened. He produced a report in November 1981 that led to the introduction of many procedures to improve trust and understanding between the police and ethnic minority communities.

Lord Scarman recommended “racially prejudiced” behaviour should be made a specific offence under the Police Discipline Code with offenders liable to dismissal.

His report led to an end to the Sus law, the creation of the Police Complaints Authority and police/community consultative groups as well as new approaches to police recruitment and training.

The report said there was “no doubt racial disadvantage was a fact of current British life”. But that “institutional racism” did not exist in London’s Metropolitan police force.

Conversely, almost 18 years later, following the death of Stephen Lawrence and the police mishandling of his case, Sir William MacPherson was commissioned to lead the public inquiry into Stephen Lawrence’s murder and the allegedly corrupt police investigation. His report, published in February 1999 declared that there was indeed institutional racism in the Met Police.

Video: The Battle for Brixton

The Battle for Brixton was a pitched battle, fought between disgruntled youth, members of the community, the police and anyone who represented “the system”. Witness this history as told by those who were on the front line.

The first Brixton Riots lingered on for about three days. This documentary looks at some of the events that happened on that fateful weekend of 10 — 12 April 1981.