From the rugged shores of Newfoundland to the icy peaks of the Yukon, the land that is now Canada has a storied past, marked by the interplay of indigenous cultures, European colonisation, and a gradual, peaceful path to nationhood. Unlike many tales of nation-building, this narrative is one of complex alliances, cultural exchange, and constitutional evolution, culminating in a unique form of independence.

The French and British tug-of-war

Canada’s European chapter began in the early 16th century with the arrival of French and British explorers. Under the guidance of figures like Jacques Cartier and Samuel de Champlain, the French established their first permanent settlement in Quebec in 1608, laying the foundation for New France. Unlike its Spanish and British counterparts further south, this colony was less about territorial conquest and more about fur trading and alliances with Indigenous peoples.

Meanwhile, after a series of intermittent settlements, the British solidified their presence in the early 17th century. The stage was set for a centuries-long rivalry between France and Britain over North American dominance. This conflict was part of a larger global contest between these European powers, playing out across continents.

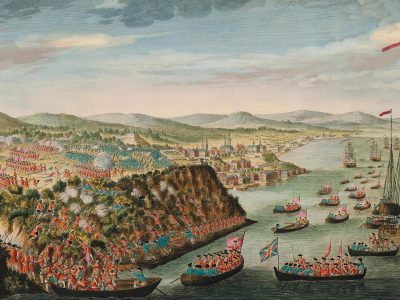

The Seven Years’ War (1756-1763), a global conflict known in America as the French and Indian War, was the climax of this rivalry. The British emerged victorious, leading to the 1763 Treaty of Paris. This treaty ceded nearly all of France’s North American territories to Britain, drastically altering the continent’s colonial landscape.

Slavery

As with most other European colonies, slavery existed in Canada, although its history and characteristics were somewhat different from the more well-known systems of slavery in the United States and the Caribbean. Slavery in Canada occurred both under French and British rule, and it involved the enslavement of both Indigenous peoples, known as Panis and Africans.

Under French rule

The French introduced slavery in Canada in the early 17th century. It was legalised in New France (the area that became Quebec, parts of Ontario, and the American Midwest) in 1709. The French primarily enslaved Indigenous peoples, who were captured in raids or bought from other Indigenous groups. These enslaved individuals were used for domestic service and labour.

Under British rule

After the British conquest of New France in 1763, the practice of slavery continued. The British, like the French, enslaved both Indigenous peoples and Africans. However, the number of enslaved Africans began to increase under British rule. Slavery in British North America was not as extensive as in the American South or Caribbean colonies, mainly because the economic conditions in Canada did not support the large-scale plantation agriculture that characterised these regions.

Abolition

The movement to end slavery gained momentum in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The Act Against Slavery was passed in Upper Canada (now Ontario) in 1793, marking the beginning of the end of slavery in Canada. This act, introduced by John Graves Simcoe, did not immediately free all enslaved people but prevented the importation of new slaves and mandated the eventual emancipation of the children of those who were enslaved at the time. Slavery effectively ended in Canada in 1834 when the British Empire abolished slavery throughout its territories with the Slavery Abolition Act.

Canada and the Underground Railroad

In the 19th century, Canada became known as the terminus of the Underground Railroad, a network of secret routes and safe houses used by African-American slaves to escape into free states and Canada. Many escaped slaves found refuge in Canada, where slavery was no longer legal, and they helped build and enrich Canadian communities.

The history of slavery in Canada is an important and often overlooked part of the country’s history, reflecting complex interactions between European colonisers and Indigenous peoples, as well as Canada’s role in the broader history of the Atlantic slave trade and abolition movements.

A patchwork of cultures and loyalties

Post-Treaty, Britain faced the challenge of governing a vast and diverse territory. The Quebec Act of 1774 was a significant step, granting religious freedom to Catholics and allowing French civil law to coexist with British criminal law. This move, though controversial among some in the Thirteen Colonies, was pivotal in gaining the loyalty of French Canadians.

As the American Revolutionary War reshaped the continent’s southern borders, Canada became a refuge for Loyalists fleeing the United States. This influx led to the creation of new colonies like New Brunswick. It greatly influenced the cultural and political makeup of the region.

The War of 1812 further tested Canada’s identity and defences. American invasions were repelled with a mix of British, local, and indigenous forces, a crucible in which a distinct Canadian identity began to be forged.

The Road to Confederation

By the mid-19th century, the call for greater self-governance grew louder. The Rebellions of 1837-38 in Upper and Lower Canada were symptomatic of a wider dissatisfaction with the colonial governance system. These uprisings, though unsuccessful, sparked significant reforms, including the eventual union of Upper and Lower Canada into the Province of Canada in 1840.

The 1860s brought a turning point. Political deadlock within the Province of Canada and external threats prompted leaders to consider a grand union. The Charlottetown Conference of 1864, initially aimed at discussing a maritime union, became the birthplace of a bigger idea – a confederation of British North American colonies.

On 1 July 1867, the British North America Act (later renamed the Constitution Act) came into effect, creating the Dominion of Canada. This new nation, initially encompassing Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia, was a groundbreaking experiment in nation-building – a federation with significant autonomy, yet still under the British crown.

A gradual path to full sovereignty

Canada’s path to complete sovereignty was unique. Unlike many nations, which achieved independence through revolution or decolonisation, Canada’s journey was marked by gradual constitutional amendments and negotiations.

Key milestones included the Statute of Westminster in 1931, granting legislative independence to Canada and other dominions, and the gradual repatriation of constitutional powers over the course of the 20th century. The final step came in 1982 with the patriation of the Constitution, including the new Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, a bill of rights that entrenched citizens’ rights and freedoms in the Constitution.

Canada Day: A celebration of nationhood

Canada Day is celebrated on 1 July and commemorates the anniversary of the Confederation. It’s a day of reflection on Canada’s unique path to nationhood, a journey marked not by violent upheaval but by careful negotiation and constitutional evolution.

Conclusion

Canada’s story is one of diverse peoples coming together under a shared vision of governance and identity. Canada’s history is a testament to the power of diplomacy and progressive constitutionalism from the early days of European rivalry and Indigenous alliances to the peaceful negotiations of the 20th century. As Canadians celebrate their national day, they remember a past filled with challenges and triumphs. This history has shaped a nation known for its diversity, tolerance, and commitment to peace.