In 1781 over 100 enslaved Africans were thrown overboard the Zong slave ship to allow the slave owners to collect insurance money on their human commodities. This is one of the most egregious acts of inhumanity in Black history.

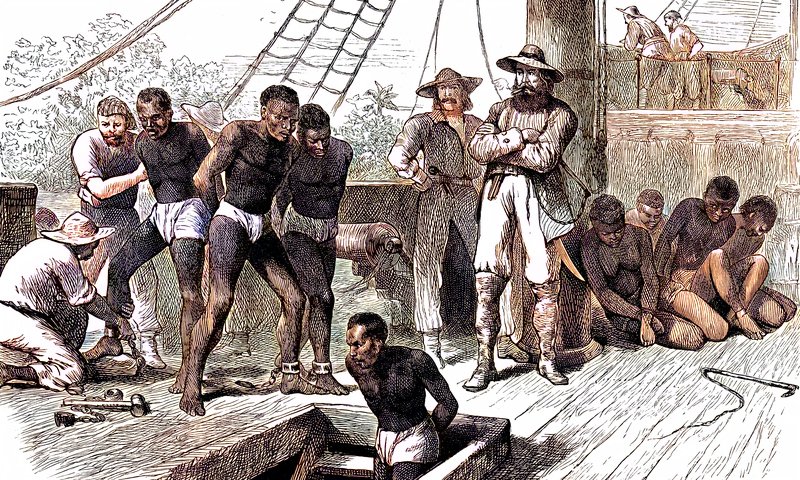

The slave trade brought vast wealth to British ports and merchants but conditions were horrific. Enslaved people were transported on the ‘Middle Passage’ of the triangular trade route. Many did not survive the horrendous conditions on board the ships.

Background

A Dutch ship named the Zorgue was seized by the British in 1781 off West Africa along with 244 Africans on board. It was then bought by the captain of a Liverpool slave ship on behalf of his Liverpool owners. Now renamed the Zong and with a new make-shift crew, captained by Luke Collingwood, the vessel traded at Cape Coast and Accra, accumulating a final complement of 442 enslaved Africans.

Since human chattel was such a valuable commodity at that time, many captains took on more slaves than their ships could hold to increase their profits. The ship and its human cargo, now insured with underwriters in England for £8,000, sailed for supplies to São Tomé, an island off the west coast of Africa, leaving there for Jamaica on 6 September 1781. Captain Collingwood was ill throughout much of the voyage.

The Zong massacre

Due to a navigational error, the ship missed its destination in the Caribbean and had to spend an extra three weeks at sea. Drinking water was growing short and sickness had spread among the enslaved people and crew.

Faced with the prospect of losing many of the slaves to disease, malnutrition and thirst and growing desperate, the crew decided to discard some of the cargo to save the ship. This action would allow the ship owners to claim for the loss on their insurance British law. If the Africans had died on board, the traders wouldn’t be eligible to receive the insurance money on their human cargo.

By justifying this as a necessary measure to save drinking water and ensure the survival of the rest of the cargo men, women and children were thrown ruthlessly into the ocean. Some, realising their fate, chose to commit suicide rather than be tossed like rubbish. Around 142 enslaved Africans died.

The Zong arrived in Black River, Jamaica, on 22 December. Captain Luke Collingwood died shortly afterwards, and the surviving African captives were advertised for sale. The ship’s log – the formal record of everything that happened on the ship – had mysteriously disappeared.

Insurance claim and subsequent trials

James Gregson, the ship’s owner, filed an insurance claim for the loss of his human cargo. Gregson argued that the Zong did not have enough water to sustain both crew and human commodities.

The insurance underwriter, Thomas Gilbert, disputed the claim citing that the Zong had 420 gallons of water aboard when she was inventoried in Jamaica. Despite this, the Jamaican court in 1782 found in favour of the owners. The insurers appealed the case in 1783 and in the process provoked a great deal of public interest and the attention of abolitionists in Great Britain.

Before the Zong case in 1783, the legal question of how insurance claims were affected should Africans be deliberately killed had not arisen. For that was all the Zong affair was concerned with: insurance.

The legal disputes between the insurers and the owners of Zong came to the notice of abolitionist Olaudah Equiano. At that point, Equiano was in his late 30s and making a new life for himself in London. On hearing of the Zong trial, Equiano brought it to the attention of Granville Sharp, a passionate crusader for social justice who was committed to challenging slavery. Sharp regarded the Zong deaths as a massacre, rather than a legal dispute about maritime insurance practices.

Publicity surrounding the Zong Massacre and the first case led William Murray, the Earl of Mansfield and the Lord Chief Justice of the King’s Bench, the highest court in Great Britain, to order a second trial. Mansfield presided and ruled in favour of the insurers. He also held that the cargo had been poorly managed as the captain should have made a suitable allowance of water for each slave.

The verdict was inevitable as slavery was still widely regarded as a legitimate business interest. Sharp attempted to have criminal charges brought against the captain, crew, and the owners but was unsuccessful. Great Britain’s Solicitor General, Justice John Lee, refused to take up the criminal charges exclaiming:

“What is this claim that human people have been thrown overboard? This is a case of chattels or goods. Blacks are goods and property; it is madness to accuse these well-serving honourable men of murder. They acted out of necessity and in the most appropriate manner for the cause. The late Captain Collingwood acted in the interest of his ship to protect the safety of his crew. To question the judgement of an experienced well-travelled captain held in the highest regard is one of folly, especially when talking of slaves. The case is the same as if wood had been thrown overboard.’

Legacy of the Zong massacre

A few months after the Zong trial, the Society of Friends began to campaign against slavery, and the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was founded four years later. Thanks largely to their efforts, in which the story of the Zong featured prominently, Parliament outlawed the Atlantic slave trade in 1807 and abolished slavery throughout the British Empire in 1833.

The deliberate killings of Africans during voyages of slave ships did not end following the Zong. They increased in the early 19th century following the abolition of the slave trade. When Royal Navy vessels chased suspected illegal slave ships, the slavers’ crews were often prepared to throw Africans overboard rather than be caught with slaves on board and have the vessels impounded.