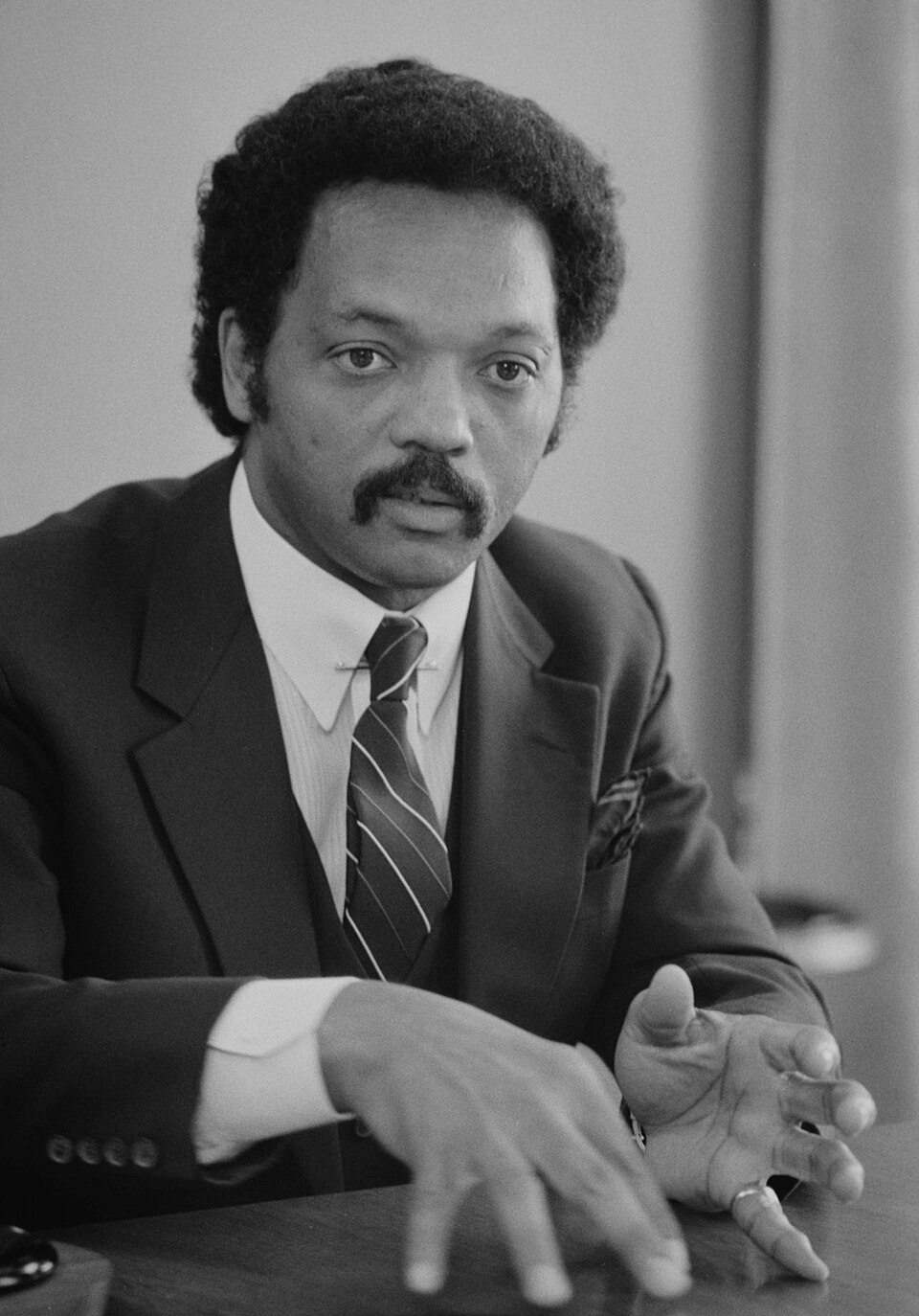

October 8, 1941 – February 17, 2026

Civil rights leader, Baptist Minister, presidential candidate, and voice of the voiceless

Origins: A son of the South

Jesse Louis Burns came into the world on 8 October 1941, in Greenville, South Carolina, under circumstances that might have defined a lesser man as a footnote. His mother, Helen Burns, was a teenager and unmarried. His father, Noah Louis Robinson, was a thirty-three-year-old married neighbour who never married her. It was a beginning defined by the twin hardships of illegitimacy and poverty. Hardships were compounded by the severe social codes of the Jim Crow South, where a Black child’s prospects were circumscribed from birth.

When Helen Burns married Charles Henry Jackson, Jesse took his stepfather’s name and became Jesse Jackson. It was a surname he would make famous worldwide. In high school, Jackson proved himself an honours student with rare gifts. He was intellectually sharp, physically imposing, and possessed of a preacher’s instinct for an audience. Those gifts earned him a football scholarship to the University of Illinois, though he later transferred to the Agricultural and Technical College of North Carolina, where he graduated in 1964.

From there, he began studies at the Chicago Theological Seminary, studies he would eventually set aside, because history called him elsewhere.

Awakening: The Civil Rights Movement

Jackson’s political education began before his college years were even finished. In 1960, while home from school, he joined seven other young Black Americans in a sit-in at the Greenville Public Library — a facility that allowed only white patrons. He was arrested. It would be the first of many confrontations with authority, and the first proof that Jesse Jackson was someone who, when he saw an injustice, would walk toward it rather than away.

By 1965, Jackson had entered the orbit of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. He marched with King in Selma, Alabama, as protesters demanded the right of Black Americans to vote, a right the nation had promised them a century earlier and had withheld ever since. Recognising Jackson’s gifts, King appointed him to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and eventually entrusted him with leading Operation Breadbasket, the SCLC’s Chicago-based economic empowerment initiative. The program organised boycotts against businesses that excluded Black workers and vendors, translating the moral energy of the movement into economic leverage.

Jackson was in his mid-twenties and already a force. He was also, by many accounts, ambitious to a degree that sometimes annoyed his elders, including King himself. The tensions were real and documented. But King kept him close, because the young man from Greenville could move a crowd like almost no one else alive.

The day that changed everything

On the evening of 3 April 1968, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered what would become his final speech in Memphis, Tennessee, where sanitation workers were on strike. The following afternoon, 4 April, King and members of his inner circle gathered at the Lorraine Motel as they prepared to leave for dinner. Jesse Jackson was there among the movement’s younger leaders, along with Ralph Abernathy, Hosea Williams, and others.

Shortly after 6 p.m., as King stood on the second-floor balcony outside his room, an assassin’s bullet struck him. Jackson, who was in the motel courtyard below the balcony, rushed toward the scene with the others as chaos erupted. He was 26 years old, and in a single instant the man who had served as his mentor and moral compass was gone.

What happened in the immediate aftermath has long been contested. Jackson later said he was among those who reached King as he lay dying; some other witnesses recalled events differently. What is not disputed is that King’s assassination marked a turning point in Jackson’s life and public role. On 30 June 1968, he was ordained as a Baptist minister by the Rev. Clay Evans — and from that point forward, he threw himself even more fully into the struggle King had led.

Building an institution: PUSH and the Rainbow Coalition

The years after King’s death brought fracture. Jackson clashed repeatedly with the leadership of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, where disagreements over authority, strategy, and control of Operation Breadbasket in Chicago grew increasingly bitter. In 1971, amid those disputes, he was suspended from the organisation. Rather than reconcile, Jackson stepped away, and in December of that year, he founded Operation PUSH — People United to Save Humanity — creating an independent vehicle for the economic and political activism he had once pursued within King’s movement.

PUSH became Jackson’s vehicle for economic justice in Black communities, organising boycotts, running voter registration drives, creating a platform through a weekly radio program, and recognising Black achievement in business and civic life. It was headquartered in Chicago, the city that would remain his base of operations for the rest of his life.

Then came his most daring institutional creation. In 1984, alongside his first presidential campaign, Jackson founded the National Rainbow Coalition — an organisation whose very name announced its philosophy. The Coalition sought to unite African Americans, white progressives, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, women, and LGBTQ Americans into a single political force. It was an argument that the Democratic Party had spent decades failing to make: that the dispossessed of every colour had more in common with each other than with those who profited from keeping them divided.

“Our flag is red, white and blue,” Jackson declared, “but our nation is a rainbow — red, yellow, brown, Black and White — and we’re all precious in God’s sight.”

In 1996, Operation PUSH and the National Rainbow Coalition merged to form the Rainbow PUSH Coalition, the organisation Jackson would lead for the next two decades.

Running for President: 1984 and 1988

In November 1983, Jesse Jackson announced his candidacy for the Democratic presidential nomination, becoming only the second African American — after Shirley Chisholm r Shirley Chisholm in 1972 — to mount a serious nationwide campaign for the presidency. He did so with little backing from major party leaders and limited national campaign infrastructure, and many within the Democratic establishment doubted he could mount a competitive run. He proved them wrong.

His 1984 campaign registered more than a million new voters, won roughly 3.3 million votes, and placed third overall in the primary, carrying several contests, including Louisiana, the District of Columbia, and South Carolina. The campaign was also shadowed by controversy: in remarks later reported by The Washington Post, Jackson referred to New York as “Hymietown,” a derogatory slur for Jewish people. He initially disputed the account but later apologised publicly, and the episode damaged his relationship with many Jewish American voters.

His 1988 campaign marked a far greater breakthrough. Jackson won nearly seven million votes, carried numerous primaries and caucuses across the country, and finished second in the nomination race behind Michael Dukakis, ultimately securing just over a thousand delegates at the Democratic National Convention. At that convention, he delivered one of the most celebrated speeches of his career, closing with the phrase that had already become his campaign’s defining call: “Keep hope alive.”

Jackson’s campaigns helped reshape Democratic coalition politics in ways still visible today. He made civil rights, voting access, economic inequality, and the inclusion of minority constituencies central to a modern national campaign, and he was among the first major presidential contenders to speak openly in support of gay and lesbian Americans as part of a broader civil-rights agenda. His campaigns also strengthened the party’s use of proportional delegate allocation in presidential primaries — reforms adopted after the 1970s but reinforced by insurgent campaigns like his — helping ensure that outsider candidates could accumulate delegates and remain competitive deep into the primary season. Political historians often view this environment as one that later enabled coalition candidates, such as Barack Obama, to build viable paths to the nomination.

Jackson himself later reflected on his runs without bitterness:

“No, it doesn’t hurt, because I was a trailblazer, I was a pathfinder. I had to deal with doubt and cynicism and fears about a Black person running… Even Blacks said a Black couldn’t win.”

Diplomat without portfolio

No account of Jesse Jackson’s career would be complete without his unusual role as a self-appointed ambassador to the world’s trouble spots. Operating outside official channels — and sometimes to the frustration of sitting presidents — Jackson repeatedly inserted himself into international crises and, more often than not, produced results.

He negotiated the release of a downed American Navy pilot from Syria in 1984. He travelled to Cuba and secured the release of political prisoners. He flew to Belgrade during the Kosovo conflict in 1999 and won the release of three US servicemen held by Slobodan Milosevic. Long before these became mainstream foreign policy positions, Jackson was publicly advocating for direct peace negotiations between Israelis and Palestinians, for ending apartheid in South Africa, and for democratic reforms in Haiti.

His consistent argument was simple: if people are suffering and talking might help, then you go and talk. Official protocol took a back seat to human lives.

The later years

Jackson never stopped. Through the 1990s and 2000s, he remained an inescapable presence at every flashpoint in American racial politics — demanding investigation into the Florida election irregularities in 2000, calling for the arrest of Trayvon Martin’s killer in 2012, pushing back against what he characterised as President Trump’s emboldening of racist sentiment. He hosted a program on CNN. He delivered commencement addresses at universities across the country. He organised voter registration drives through Appalachia and the Mississippi Delta.

In 2000, President Bill Clinton awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honour. Over the course of his career, Jackson received more than forty honorary doctoral degrees from institutions ranging from Howard to Yale to Oxford.

He won election as a shadow senator for the District of Columbia in 1990, using that platform to advocate for DC statehood. He mentored a generation of political operatives who would go on to remake the Democratic Party: Minyon Moore, who co-chaired the 2024 Democratic National Convention; Donna Brazile, who served as interim DNC Chair; and many others whose names are less famous but whose work carries his imprint.

When Barack Obama was elected president in 2008, cameras caught Jesse Jackson in the crowd at Grant Park in Chicago, tears streaming down his face. Asked afterwards what he felt, he reached back to the movement: “To get here, we’ve gone through some bloody trails of terror to get here. Some good people, Medgar Evers, Dr King at 39. We paid a price to get here.”

Family

In 1962, Jackson married Jacqueline Brown, who remained his partner and companion for more than six decades. Together, they had five children: Santita, Jesse Jr., Jonathan, Yusef, and Jacqueline. A sixth child, Ashley, was born from an extramarital relationship — a revelation that became public in 2001, producing significant controversy and a period of painful reckoning for his family and his public standing.

His son, Jesse Jackson Jr., was elected to represent Illinois in the US House of Representatives, but his political career ended in 2012 with his resignation and subsequent legal troubles.

Illness and twilight

In 2017, Jackson made public what had been privately known for some time: he had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. He framed it, characteristically, as a challenge rather than a defeat. “I am taking it one day at a time,” he said, and he continued working, attending rallies, issuing statements, and showing up.

In April 2025, his Rainbow PUSH Coalition disclosed that he had been further diagnosed with progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), a rare and severe neurodegenerative condition affecting movement, balance, and the ability to swallow. In November 2025, he was hospitalised in Chicago for the condition and related complications.

He did not return to public life.

Death and legacy

The Rev. Jesse Louis Jackson Sr. died peacefully on the morning of Tuesday, 17 February 2026, in Chicago, surrounded by his family. He was 84 years old. His family posted a statement that said what needed to be said simply:

“Our father was a servant leader — not only to our family, but to the oppressed, the voiceless, and the overlooked around the world. We shared him with the world, and in return, the world became part of our extended family. His unwavering belief in justice, equality, and love uplifted millions, and we ask you to honor his memory by continuing the fight for the values he lived by.”

The Rev. Al Sharpton, who considered Jackson his mentor, said the nation had “lost one of its greatest moral voices” — a man who “carried history in his footsteps and hope in his voice.” Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson called Jackson “an architect of the soul of Chicago.”

Jesse Jackson’s legacy is complicated, as the legacies of large, driven, contradictory people always are. He was a preacher’s son who was also a preacher. He was a builder of institutions and, at times, a test of those institutions. He was capable of inspiring rhetoric and wounding words in equal measure. He was self-promoting, and he genuinely promoted the cause of millions who had no other promoter.

What is not complicated is what he built. The Rainbow Coalition’s philosophy of multiracial democratic politics is the architecture of the modern Democratic Party. The delegate rules he fought for created the conditions that allowed Barack Obama and Kamala Harris to reach the heights they did. The million voters he registered in 1984 voted in every election thereafter. The hostages he brought home came home.

He once described himself with an image that has lasted: “I’m a tree shaker, not a jam maker.” The trees he shook are still falling.

Jackson is survived by his wife, Jacqueline; his children, Santita, Jesse Jr., Jonathan, Yusef, Jacqueline, and Ashley; and his grandchildren.

Leave a Reply