The Notting Hill Race riots were the result of a campaign of attacks on the Caribbean residents in a bid to drive them out of their homes and ultimately out of Britain. Much like the 1919 race riots, the growing Black presence in Britain was a major factor in these events.

Although dubbed the Notting Hill race riots, these riots started in Shepherds Bush and adjacent Notting Dale and spread to several areas in Notting Hill, Kensal New Town, Paddington and Maida Vale.

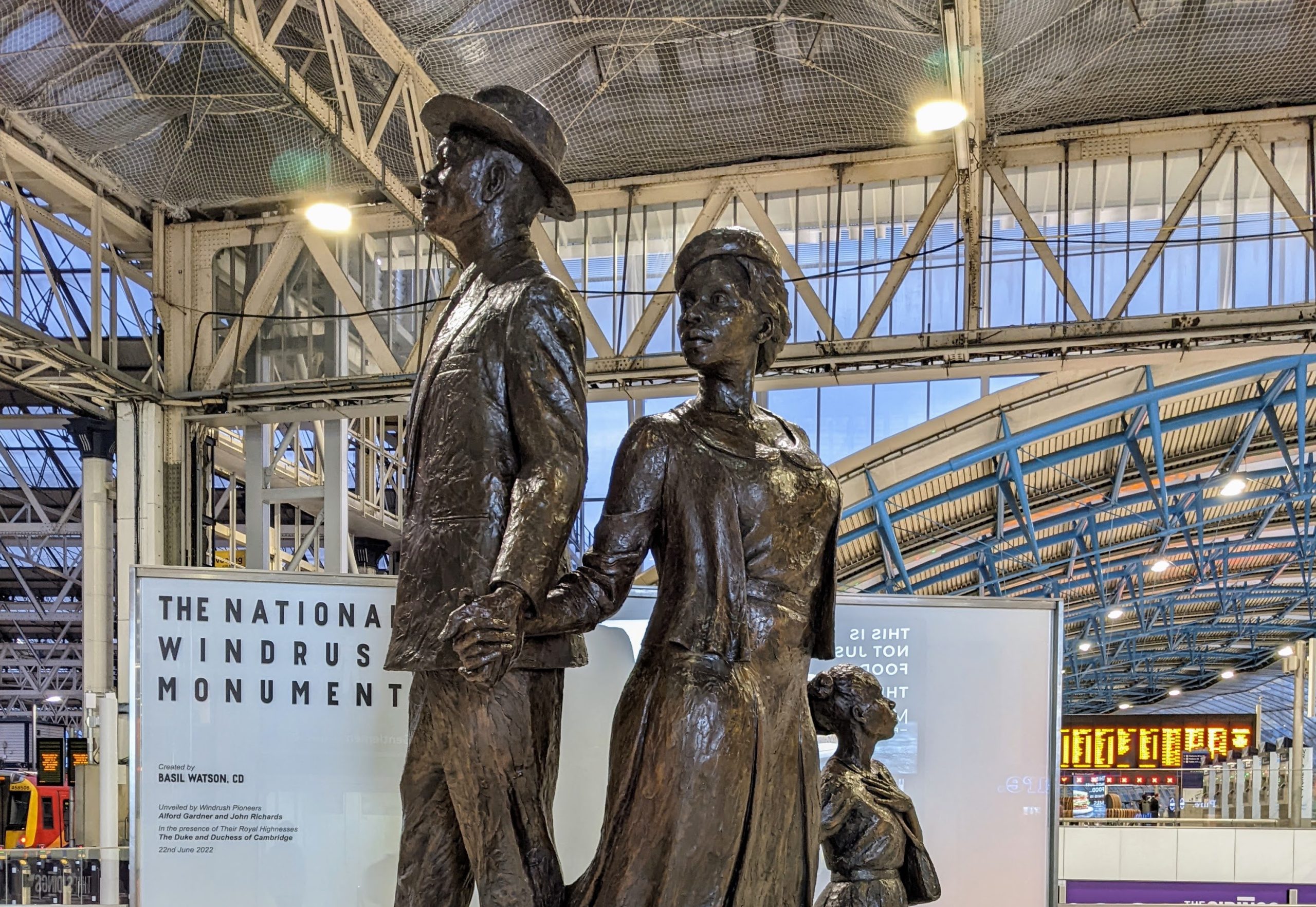

Arrival of the Windrush Generation

Following the first arrival of the SS Empire Windrush on 22 June 1948, more than 300,000 people from the Caribbean settled in Britain. These Black settlers were encouraged by the British Government to come to the UK to fill jobs due to Britain’s post-war labour shortage.

Many of the new arrivals settled in London and by the 1950s, Brixton and Notting Hill had the largest population of Afro-Caribbean people in Britain. Back then Notting Hill was a working-class slum area known as ‘Notting Dale’.

Some landlords refused to rent to Black families, advertising for rooms to rent specifying ‘no coloureds’ while others crammed several people into one room and charged over the odds for deplorable living conditions.

Caribbean people lived alongside the white working-class, and it was an uncomfortable existence.

Thirteen short years after more than 16,000 people from the Caribbean fought with the British against the Nazis and a mere, 10 years after they had invited them to come to the motherland to fill jobs, Caribbean people were facing covert and overt racism.

Overt racism

Black people in the area often experienced hostilities from white working-class residents, however during the summer of 1958, gangs of Teddy Boys became increasingly overt about their aggressive intentions toward anyone who was Black.

During this period, Notting Hill was a stronghold for fascist politician Oswald Mosley’s Union Movement, a far-right movement that urged the local white working-class population to “Keep Britain White”.

In 1958-59 under the banner of “Keep Britain White” attacks on the Black communities of Notting Hill, began with the intention to drive them out of their homes. There were many attacks by gangs of white youths on Black people and Black businesses.

What started the Notting Hill race riots?

The riots were a culmination of a series of events deliberately instigated by the “Keep Britain White” mobs and Teddy Boys who roamed Notting Hill and Shepherds Bush, “nigger hunting”.

As “nigger hunting” spread, a growing number of active forces became involved in several areas. Fascist agitators stirred up the racists in and around Notting Hill, where the White Defence League and the Union Movement held meetings and distributed leaflets.

There was a prevailing atmosphere of ‘menace and fear’ that permeated the area.

On 20 August property owned by Black people was vandalised and the owners were physically harassed by a 400-strong mob of white men.

Violence escalated during the early hours of Sunday morning, 24 August, when nine Teddy Boys stuffed themselves into a car and cruised the streets armed with iron bars, table legs, pieces of wood and a knife. Their cowardly strategy was to attack Black people walking alone or in twos at most. They managed to attack five Black men in Shepard’s Bush, leaving three seriously injured and hospitalised. The nine Teddy Boys were eventually locked up for four years.

Things intensified on 29 August 1958 after Majbritt Morrison, a young Swedish woman, was seen arguing outside Latimer Road Tube station with her Jamaican husband, Raymond. A white crowd showed up to defend Majbritt (who didn’t want to be defended), and a scuffle broke out between them and some of Raymond’s Caribbean friends.

By the following evening, a 300 to 400 strong white mob were rampaging through the streets of Notting Hill armed with weapons, including sticks and butcher’s knives, shouting “Down with the niggers” and “Go home you black bastards”, breaking into homes and attacking any Black person they could find.

Fighting back

The disturbances had spread to several other places. Under the railway arches near Latimer Road Underground Station a gang of 100 youths with sticks, iron bars and knives, had gathered. There were fights also on Harrow Road and in Kensal Rise. The rioting continued day and night. Most Black people stayed at home. But many others had mobilised as the attacks on their homes intensified, they fought back with machetes and home-made Molotov cocktails.

In the book Forbidden Britain a Notting Hill resident recounts his story of fighting back:

“Well, black people were so frightened at that time that they wouldn’t leave their houses, they wouldn’t come out, they wouldn’t walk the streets of Portobello Road. So we decided to form a defence force to fight against that type of behaviour and we did. We organized a force to take home coloured people wherever they were living in the area. We were not leaving our homes and going out attacking anyone, but if you attack our homes, you would be met, that was the type of defence force we had. We were warned when they were coming and we had a posse to guard our headquarters.”

“When they told us that they were coming to attack that night I went around and told all the people that was living in the area to withdraw that night. The women I told them to keep pots, kettles of hot water boiling, get some caustic soda and if anyone tried to break down the door and come in, to just lash out with them. The men, well we were armed. During the day they went out and got milk bottles, got what they could find and got the ingredients of making the Molotov cocktail bombs. Make no mistake, there were iron bars, there were machetes, there were all kinds of arms, weapons, we had guns.”

“We made preparations at the headquarters for the attack. We had men on the housetop waiting for them, I was standing on the second floor with the lights out as look-out when I saw a massive lot of people out there. I was observing the behaviour of the crowd outside from behind the curtains upstairs and they say, ‘Let’s burn the niggers, let’s lynch the niggers.’ That’s the time I gave the order for the gates to open and throw them back to where they were coming from. I was an ex-serviceman, I knew guerrilla warfare, I knew all about their game and it was very, very effective.”

The metropolitan police were noted to have been generally passive towards the situation advising Black residents to stay home. This changed when many white teenagers began to harass the local police for protecting Black residents. In fact, there were reports of police officers being assaulted during the carnage. The mob shouted at them: “Mind your own business, coppers. Keep out of it. We will settle these niggers our way. We’ll murder the bastards.” The ‘lynch mob’ exchanged blows with black people and the police.

Black people were literally fighting for their lives, their homes and businesses and had to be continuously alert.

On 1 September in the Notting Dale area an Antiguan student, Seymour Manning, was attacked and punched and kicked to the ground by three white men. He managed to flee and was chased into Bramley Road. He was nearly overtaken and ran into a greengrocer’s shop.

The shopkeeper’s wife appeared in the doorway and locked the door behind her. Keeping Seymour safe inside she turned to face the thugs. She continued to face down what quickly grew to be a large angry crowd until the police arrived.

Aftermath

The riots lasted until 5 of September when police eventually gained control. Around 140 people were arrested, mainly white but some Black victims who had been armed for self-defence were swept up too.

At the time senior police officers tried to dismiss the Notting Hill race riots as the work of “ruffians, both coloured and white” hellbent on hooliganism.

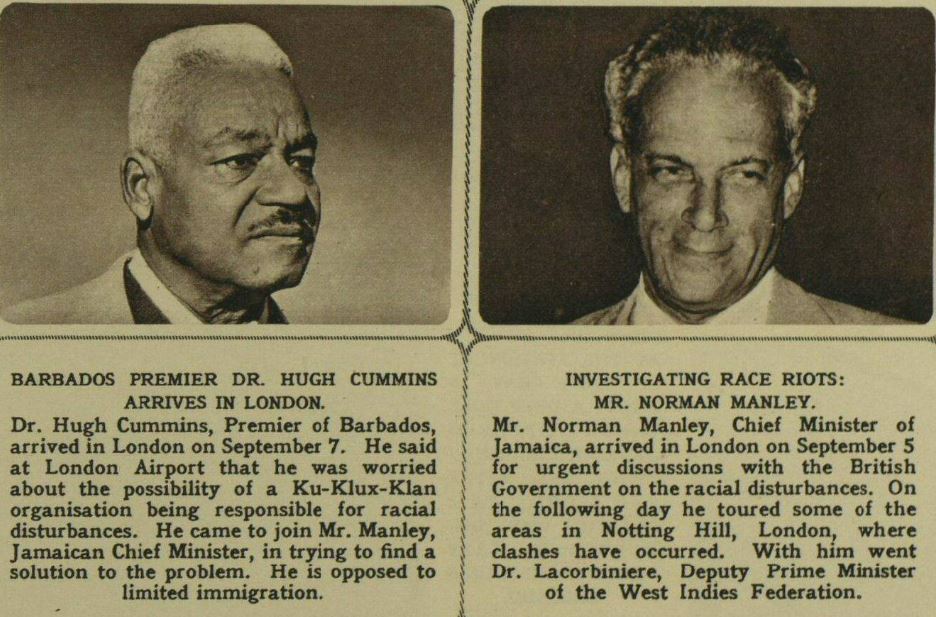

News of the riots travelled back to the Caribbean. On 5 September, West Indian political leaders Norman Manley, Chief Minister of Jamaica, and Dr Carl LaCorbiniere, the Deputy Prime Minister in the Federal Government of the West Indies, arrived in London. Dr Hugh Cummins, the Prime Minister of Barbados, arrived in London on 7 September.

The leaders had talks with the British government and attended meetings to speak with their fellow countrymen in London.

At a meeting in Notting Hill attended by 2000 people, local North Kensington M.P., George Rogers, who represented the Labour Party, was shouted down by the crowd due to his controversial views. The MP wanted to restrict the entry of Caribbean migrants into Britain. The audience called him a fascist, a liar and a fool.

At that same meeting, Norman Manley told the audience, “We are here to give you advice and to challenge decent British public opinion to stamp out things that would shame even a Southern State in America.”

The leaders also visited other troubled areas in London and Nottingham.

Legacy

Four months after the riots, the very first London Caribbean Carnival was held indoors at St Pancras Town Hall in January 1959 in response to the racial attacks and increased tensions.

On 17 May 1959, less than a year after the riots, Antiguan carpenter Kelso Cochrane was walking home when a gang of white youths surrounded him, called him derogatory names, beat him up and stabbed him. His murder is marked as the first racially motivated killing after the Windrush generation migrated to Britain.

My grandad was a part of these riots. My grandparents fought every day for a place in racist Britain. I hate that people forget how our parents and grandparents suffered to make a place for us.

Notting Hill has been gentrified and carnival has lost its meaning. Young people go there and fight and give the festival a bad name. Their parents obviously don’t tell them how hard black people fought for a place in this godforsaken place.