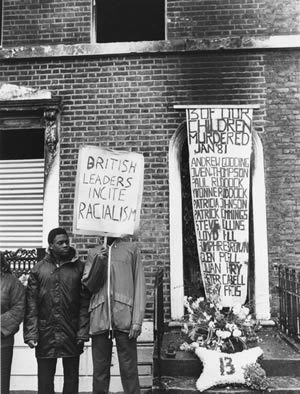

On Sunday, 18 January 1981, a fire broke out in a house in New Cross Road, Deptford, South East London, killing 13 people and marking a massive change for black people in Britain.

Fire in New Cross

Yvonne Ruddock and Angela Jackson were celebrating their 16th and 18th birthday, respectively, at Yvonne Ruddock’s house when a fire started in the front room of the two-storey house. More than 50 of the 200 guests were still at the party when the blaze took hold.

Some youngsters were trapped, and others jumped from the upper floors to escape.

Thirteen people died in the blaze, and another, Anthony Berbeck, committed suicide 18 months later in July 1983, aged 20, having been traumatised by the tragedy. His sister Jennifer is a member of the New Cross Fire Families Committee, which commemorates the blaze that claimed the young lives. Twenty-seven others were seriously injured, and an Inquest into the fire was held in Apr 1981 and again in 2004. No one to date has been charged in relation to the fire, an open verdict being delivered on both occasions.

Racism in the 70s and 80s

The fire was originally thought to be a racist arson attack. On the first day of the investigation, a police officer reported to Yvonne’s mother, Armza Ruddock, that people had seen a man throwing a petrol bomb through a window on the ground floor of the house and then run away. This news spread through the black community like wildfire. We could all believe this story because racism was rife at this time. It was not uncommon for a black person to be shot at by white men with pellet guns whilst walking down the street.

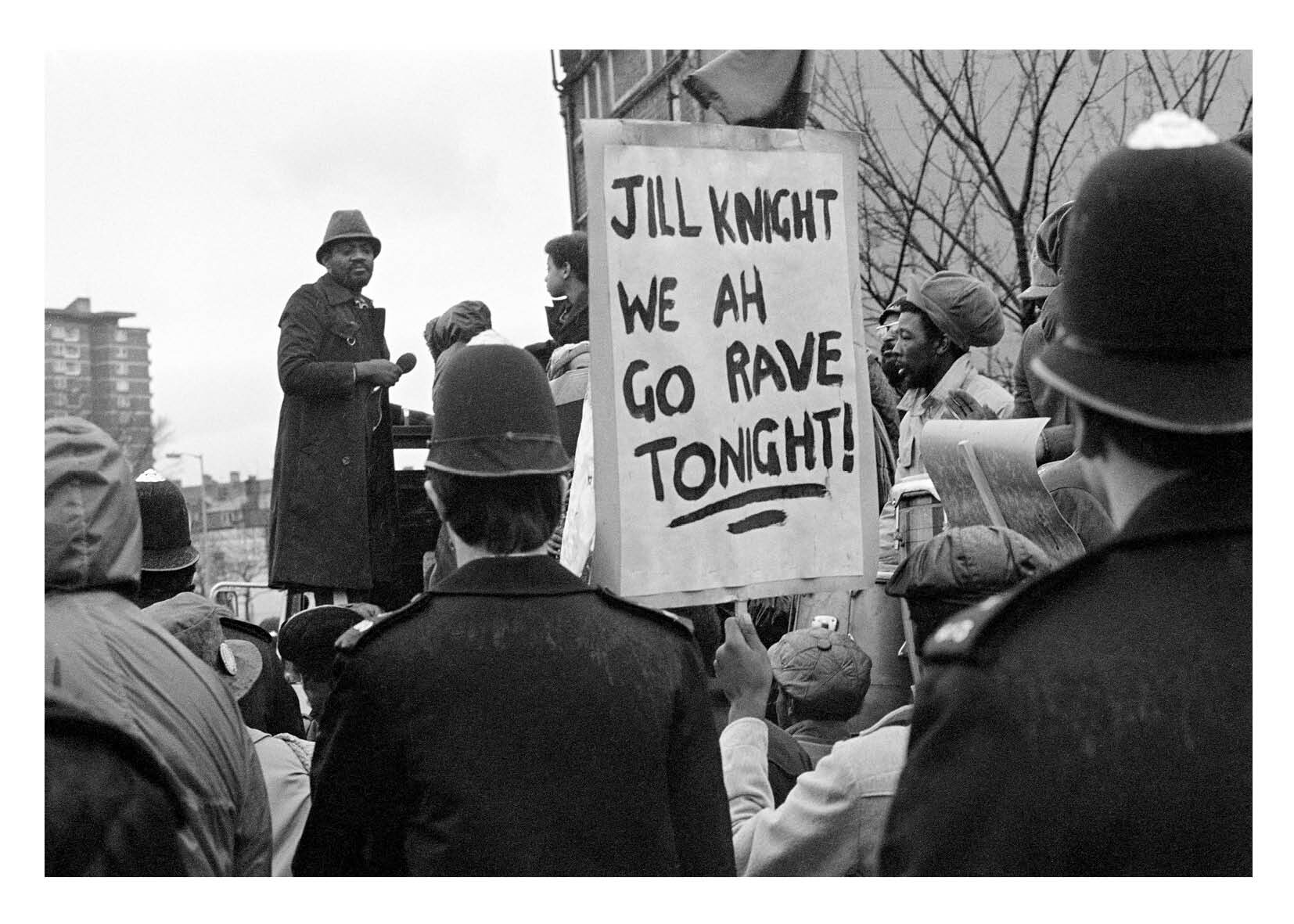

We could believe this because instead of empathising with the bereaved parents, Conservative MP Jill Knight voiced her displeasure at what she judged to be noisy black house parties.

We could believe it because, on 3 January 1971, another black house party came under attack when three petrol bombs were thrown into a house in Sunderland Road, Ladywell, injuring 22 people. In this instance, the two white racist perpetrators were caught and later jailed for the attack.

In the week after the attack, eight members of the Black Unity and Freedom Party were arrested after being hassled by police on their way back from visiting the injured in Lewisham Hospital. This harassment led to a march by 150 people to Ladywell Police Station a few weeks later and yet more arrests.

We could believe this because, on 13 August 1977, the people of Lewisham fought against racism in the Battle of Lewisham. That same year on 18 December, the Moonshot Club in St John’s Hall, Lewisham, was gutted in a firebomb attack. The club was founded by Sybil Phoenix and frequented by young Black people. Shortly after the attack, newspapers reported that burning down the Club was discussed at a National Front (NF) meeting. The NF are a British far-right political party who are opposed to non-white immigration and committed to a programme of repatriation.

Sus laws

We could believe it because the police, who were prone to racism and racial profiling, were already planning to introduce laws allowing them to target Black people further. In April 1981, three months after the New Cross fire, ‘Operation Swamp 81‘ or ‘sus laws’ (now known as Stop and Search) was brought in. The Sus Law was based on the 1824 Vagrancy Act. This meant that a police officer could stop, search and arrest people on suspicion that they might commit a crime in the future.

Far right marchs

A classic example of the indifference to Britain’s black population was the fact that the NF were allowed to march through black areas, spouting their racist propaganda. If the NF were due to march in your area, common sense dictated that all blacks be in their homes in good time.

I resented the curfew imposed on me by my parents during this time, but I understood their motivations. Whilst I was at home wrapped in cotton wool, my friends were out clashing with the NF head-on alongside the Anti-Nazi League, Socialist Workers Party members and other activist groups. The Anti-Nazi League (ANL) was set up in 1977, at a time when politics was moving to the right and when racist ideas were becoming more acceptable. They helped to reduce the NF from a growing power to a bunch of thugs.

The total lack of empathy from then Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and the Queen spoke volumes. The Queen refused requests to send a letter of condolence to the families who were still in mourning. This lack of respect was heightened by the fact that shortly after the New Cross fire, Thatcher and the Queen sent messages of condolences to white families who had lost loved ones in a disco fire in Ireland. This disregard for Black lives from the government, monarchy and the police as well as the racist reporting in the national and local press and the newly minted ‘sus laws’ helped to fuel the fire that culminated in the Brixton riots a few months later.

Black People’s Day of Action

After the New Cross Fire, John La Rose and others set up the New Cross Massacre Action Committee to support bereaved parents and to demand a full police investigation. Incensed by slow police progress and an apparent lack of sensitivity by the authorities to the children’s deaths, mass meetings were organised. Allegations arose that some of the party-goers who were interviewed by police had been forced into signing false statements under pressure.

On 25 January, a meeting was held at the Moonshot Club, followed by a demonstration of over 1000 people to the scene of the fire, blocking New Cross Road for several hours.

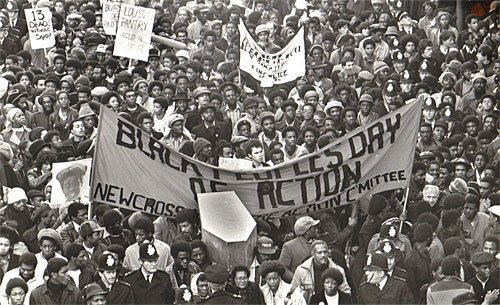

The Committee then organised a huge march for Monday, 2 March, called the Black People’s Day of Action to demonstrate against the lack of measures taken by the police in the early investigation of the fire. The march brought together activists from a range of backgrounds around the country. Black parents organisations, community organisers, angry residents, black panthers and black youth groups came together to be heard.

It turned out to be the largest ever demonstration of Black people in Britain. Up to 20,000 mostly black people marched from Fordham Park, New Cross, to Hyde Park. It took many Londoners by surprise and genuinely unnerved the establishment.

Chants on the day included ‘13 Dead, and Nothing Said’, ‘Jill Knight Set the Fire Alight’ and ‘Blood Ah Go Run If Justice No Come’.

Despite a signed agreement with the Metropolitan Police as to the route the march would take, police in riot gear tried to block the march at Blackfriars Bridge. The march stewards recognised this as a planned provocation by the police and avoided the marchers being drawn into a violent clash with the police. Eventually, the truck leading the protestors managed to break through, and the march continued as planned.

Newspapers were extremely hostile to the Black People’s Day of Action, using headlines such as ‘Rampage of a Mob’ [Daily Express], and ‘The Day the Blacks Ran Riot in London’ [The Sun]. This was the year that a lot of newspapers lost money as Black people stopped buying them. The Sun newspaper not only reduced its price, but it also introduced Sun Bingo to entice people to start reading the rag again.

The New Cross fire remains an unsolved case

In 2001 as the unsolved case reached its 20th anniversary, Scotland Yard announced its largest ever reward of £50,000 for information. The families of the 14 people who died welcomed the news.

Announcing the reward Detective Chief Supt Mike Parkes of the Racial and Violent Crimes Task Force said: “There were people at that party who have never come forward to speak to us. “Their information could prove crucial to our investigation.”

Whilst some people, including members of the bereaved families, believe that the fire was started by accident following a fight at the party, others still hold on to the racist motive.

Police now believe the fire started in an armchair in the living room of the house. It is still not clear whether the fire was accidental or started deliberately. The force is also banking on new forensic techniques, helping them find previously undiscovered clues. The fire is the force’s oldest “live” murder, manslaughter or arson case.

George Francis, chairman of the New Cross Fire Parents’ Committee, who lost his 17-year-old son, Gerry, in the blaze, welcomed the reward. He says many families felt not enough was done to find the culprits responsible, “We think it was deliberate, it’s time they (the police) should come out with an answer and let us put our kids to rest.”

We remember

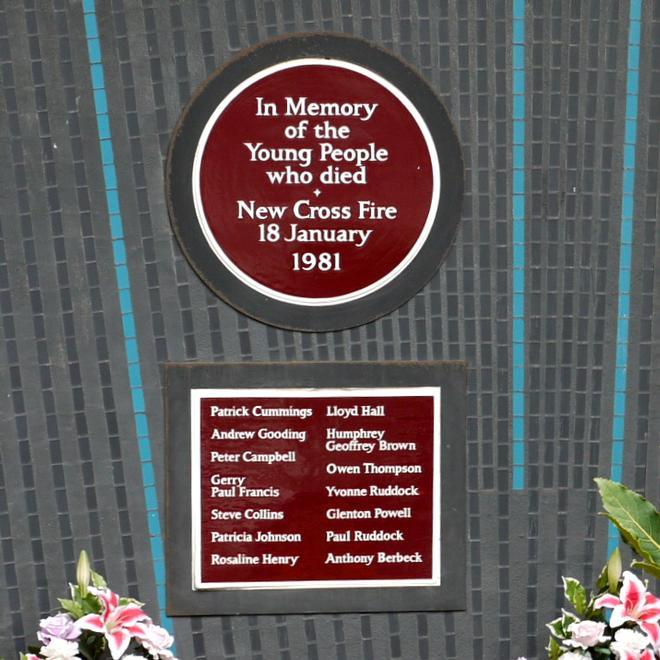

In 2011 on the 30th anniversary, a memorial was held to pay tribute to those who lost their lives. It included the unveiling of a plaque at 439 New Cross Road, where the fire took place. The ceremony was led by playwright Rex Obano. Black and minority ethnic members of the Fire Brigades Union provided an official guard of honour and marked a minute’s silence for the victims.

Also in attendance was Sybil Phoenix, who spoke of being called to the scene the morning after the fire.

“I can never ever forget, I could never forget about going to the hospital with them and then going to the police station and collecting Mrs Ruddock and taking her to my house,” she said.

There is also a plaque with the names of the deceased on a wall outside Lewisham Town Hall. This was unveiled by Sybil Phoenix on 10 February 1997. Fresh flowers are placed there quite regularly.

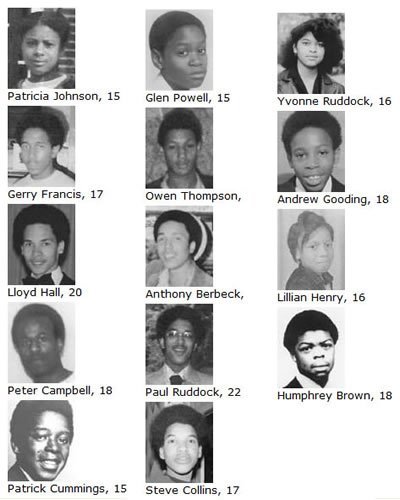

:New Cross fire victims

Andrew Gooding (18.02.1962 – 18.01.1981)

Owen Thompson (11.09.1964 – 18.01.1981)

Patricia Johnson(16.05.1965 – 18.01.1981)

Patrick Cummings (21.09.1964 – 18.01.1981)

Steve Collins (2.05.1963 – 18.01.1981)

Lloyd Hall (28.11.1960 – 18.01.1981)

Humphrey Geoffrey Brown (4.07.1962 – 18.01.1981)

Roseline Henry (23.09.1964 – 18.01.1981)

Peter Campbell (23.02.1962 – 18.01.1981)

Gerry Paul Francis (21.08.1963 – 18.01.1981)

Glenton Powell (18.01.1966 – 25.01.1981)

Paul Ruddock (19.11.1960 – 09.02.1981)

Yvonne Ruddock (17.01.1965 – 24.01.1981)

Anthony Berbeck (17.08.1962 – 09.07.1983)

The New Cross Bursary Scheme was set up in 2006 as a tribute to the young people who lost their lives in the fire. The scheme awards two young people who have been educated in Lewisham with a bursary to study at Goldsmiths University.

See also:

New Cross fire, 30 years on

Remembering the 13 young people killed in the New Cross fire

i knew paul ruddock, he was a great mate, we always hung around having a laugh, i was invited to the party , but cos i met a girl in the star & garter pub,i never went, paul was a fantastic person, and now im nearly 60 yrs old, i remember being told about the fire, he was my mate and he always made me laugh, the light went out that night, and will never come back on, too many good people lost their lives , because of a stupid thing called hatred,, R,I.P, paul & yvonne,

RIP young people.

May justice eventually be done.

[…] sent her commiserations to white families in Ireland who had lost loved ones at a disco fire¹(https://eachoneteachone.org.uk/new-cross-fire/). This callous silence towards the black community sparked the Black People’s Day of Action […]

I live on Malpas Road at the time,I was meant to be there, I was 21 on the 18th of January 1981

God bless and R.I.P to all those who died, each one a star

Rest in Peace all those who died. God bless you all, your bereaved families and all who survived. You must all never be forgotten