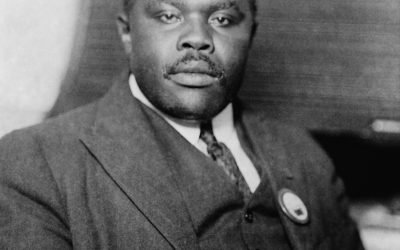

As one of Jamaica’s National Heroes, Marcus Mosiah Garvey stands out in history as one who was greatly committed to the concept of the Emancipation of minds.

Garvey’s early life

Garvey, who was born on 17 August 1887 in St. Ann, Jamaica, became famous worldwide as a leader who was courageous and eloquent in his call for improvement for Blacks. He sought the unification of all Blacks through the establishment of the United Negro Improvement Association and spoke out against economic exploitation and cultural denigration.

Garvey came to England in 1912. He worked at the offices of the African Times and Orient Review journal under the leadership of Duse Mohammed Ali, the famous Black Nationalist and journalist. The African Times and Orient Review was the first political journal produced by and for Black people ever published in Britain. It was produced during 1912-1913 and 1917-1918 on a monthly basis and was printed in Fleet Street in London.

Marcus Garvey returned to Jamaica from England in July 1914. With the help of an associate Enos J Sloly and about four others, he created the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League and launched it on 1st August 1914, which was Emancipation Day in the British-ruled Caribbean.

Universal Negro Improvement Association

Garvey aimed to organise blacks everywhere but achieved his greatest impact in the United States. He spent many years there pursuing his goal of Black Unification, tapping into and enhancing the growing black aspirations for justice, wealth, and a sense of community. During World War I and the 1920s, his Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) was the largest black secular organisation in Black history. Possibly a million men and women from the United States, the Caribbean, and Africa belonged to it.

Garvey went to New York in 1916 and concluded that the growing black communities in northern cities could provide wealth and unity to end both imperialism in Africa and discrimination in the United States. He combined the economic nationalist ideas of Booker T Washington and Pan-Africanists with the political possibilities and urban style of men and women living outside of plantation and colonial societies. Garvey’s ideas gestated amid the social upheavals, anticolonial movements, and revolutions of World War I, which demonstrated the power of popular mobilisation to change entrenched structures of power.

In 1918, nine years after the failure of his first newspaper, The Watchman, Garvey and the UNIA created the Negro World. It quickly grew from being a weekly into a worldwide phenomenon with a peak circulation of 200, 000. It featured reports from the UNIA chapter, poetry, literary excerpts, a women’s page and commentary on global events significant to Black people. It had sections in Spanish and French. Colonial authorities feared the Negro World, and it was banned in many countries such as Belize, Trinidad, Guyana, Jamaica and several African countries.

We were like crabs in a barrel, that none would allow the other to climb over, but on any such attempt all would continue to pull back into the barrel the one crab that would make the effort to climb out.

Garvey and other Black activists were partly inspired by the Irish movement for independence from English rule and thus named the UNIA headquarters Liberty Hall after Liberty Hall in Dublin, Ireland, which was the symbolic seat of the Irish Revolution. Located at 114 West 138th Street in New York City, the New York City Liberty Hall had a seating capacity of six thousand. It was dedicated on 27 July 1919. Garvey held nightly meetings at Liberty Hall that drew up to six thousand people at a time.

Garvey’s goals were modern and urban. He sought to end the imperialist rule and create modern societies in Africa, not, as his critics charged, to transport blacks “back to Africa.” He knitted black communities on three continents with his newspaper, the Negro World, and, in 1919, formed the Black Star Line, an international shipping company to provide transportation and encourage trade among the black businesses of Africa and the Americas. In the same year, he founded the Negro Factories Corporation to establish such businesses. In 1920 he presided over the first of several international conventions of the UNIA.

Marcus Garvey sought to channel the new black militancy into one organisation that could overcome class and national divisions. His ultimate dream was for the independence of all African Countries and the creation of a United States of Africa. The UNIA embarked on a plan to repatriate some Blacks from the United States and other parts of the African Diaspora back to Africa. Liberia, a country established in 1822 by the American Colonisation Society, was the intended geographical base of the UNIA’s African colonisation venture.

Although local UNIA chapters provided many social and economic benefits for their members, Garvey’s main efforts failed: the Black Star Line suspended operations in 1922 and the other enterprises fared no better. Garvey’s ambition and determination to lead inevitably collided with associates and black leaders in other organisations. His verbal talent and flair for the dramatic attracted thousands, but his faltering projects only augmented ideological and personality conflicts. In the end, he could neither unite blacks nor accumulate enough power to significantly alter the societies in which the UNIA functioned.

Garvey’s enemies

Garvey had enemies, including J Edgar Hoover and, ironically, W.E.B. Du Bois. Du Bois was an integrationist who did not support a separate Black state and repatriation. DuBois along with other members of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) organised the ‘Garvey Must Go’ campaign and colluded with the US government to have him deported.

In 1919, Hoover hired the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI) first Black agent in order to infiltrate the UNIA. The agent, James Wormley Jones, was referred to as code number 800. One of Garvey’s close confidantes, Herbert Boulin, was a spy for the FBI known as agent P-138.

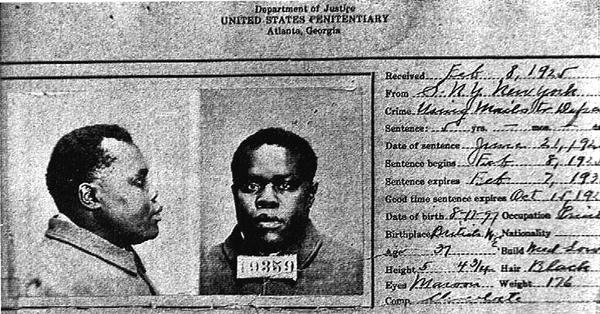

Finally, the Justice Department, encouraged by J Edgar Hoover’s Federal Bureau of Investigation and sensing his growing weakness, indicted Marcus Garvey for mail fraud. His steamship company was bankrupt, and he was convicted for fraudulently collecting money for investment in a ship that was never acquired. He was convicted in 1923 and imprisoned in 1925. His sentence was commuted by President Coolidge before Garvey was deported to Jamaica in 1927.

Garvey arrived in Kingston, Jamaica, on 10 December 1927. During this period, Garvey became a father when Amy Jacques Garvey gave birth to two sons.

People’s Political Party

In 1928, Garvey created the (PPP) which was Jamaica’s first modern political party and the first to defend the interests of the Black majority. The party’s manifesto called for official representation in the British Parliament, a minimum wage, land reform, a Jamaican university, judicial reform, a government-run electrical system, public high schools and libraries and a National Opera House.

In an effort to rebuild the international influence of the UNIA, Marcus Garvey moved to London in March 1935. In London, Garvey continued to speak extensively, appearing frequently at Speaker’s Corner Hyde Park.

Death of Marcus Mosiah Garvey

Garvey had a stroke in January 1940, which left him partially paralysed. In May 1940, leading Pan-Africanist and journalist George Padmore wrote an article stating that Garvey had died, which upset Garvey, and he suffered a second fatal stroke or heart attack.

Garvey died on 10 June 1940 in London at age 53 without having set foot in Africa.