The Industrial Revolution was a groundbreaking period that transformed Britain into an economic superpower. It brought about significant advancements in various industries, including iron production. Traditionally, the credit for revolutionising iron production has been attributed to Henry Cort, a British financier turned ironmaster. However, recent research suggests this innovation may have originated from an unexpected source – an 18th-century Jamaican foundry.

The Jamaican foundry: A hub of ironworking expertise

Historical records reveal that an ironworks near Morant Bay, Jamaica, owned by white enslaver John Reeder, became the birthplace of a groundbreaking iron production technique. This foundry, staffed by 76 black Jamaican metallurgists, showcased remarkable skills and expertise in iron manufacturing. Many of these workers were enslaved people trafficked from Africa, where iron-working industries flourished during that era.

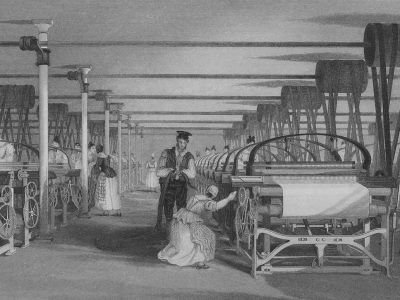

In the foundry, these skilled metallurgists introduced grooved rollers, a mechanical innovation that mechanised the laborious process of hammering out impurities from low-quality iron. Interestingly, the same grooved rollers were utilised in Jamaican sugar mills, indicating a cross-industry exchange of ideas and techniques.

Henry Cort: From Jamaica to Portsmouth

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Henry Cort, a British ironmaster facing bankruptcy, stumbled upon the Jamaican ironworks through a visiting cousin who transported seized vessels and equipment from Jamaica to England. Recognising the immense potential of the iron production process developed by the Jamaican metallurgists, Cort acquired the machinery from the foundry and shipped it to Portsmouth.

In the 1780s, Cort patented the technique, which became known as the Cort process. He is widely credited as the inventor, but this new research challenges the traditional narrative and suggests that the innovation was appropriated from the Jamaican foundry. Cort’s acquisition of the machinery and subsequent patenting of the technique marked the beginning of Britain’s ascendancy as a major iron producer.

The Cort process revolutionised iron production in Britain, propelling the nation to the forefront of the global iron trade. This innovative technique allowed wrought iron to be mass-produced from scrap iron for the first time, opening up new possibilities for industrial development.

With the advent of the Cort process, Britain witnessed the construction of iconic iron structures that defined the landscape of the Industrial Revolution. The Crystal Palace, Kew Gardens’ Temperate House, and the arches at St Pancras train station are just a few examples of the “iron palaces” that transformed the face of the country.

The Jamaican Ironworks’ success and demise

The Jamaican Ironworks, under the leadership of the black metallurgists, achieved remarkable success. By 1781, it generated an annual profit of £4,000, a substantial sum at the time. However, the promising trajectory of the foundry was abruptly interrupted when the British government, fearing rebellion, ordered its destruction, claiming that rebels could use the ironworks to fashion weapons.

Unveiling a hidden narrative

The research conducted by Dr Jenny Bulstrode, a lecturer in the history of science and technology at University College London (UCL) and author of the paper, challenges existing narratives of innovation. The story of the Jamaican metallurgists and their crucial role in the development of the iron production process sheds light on the often overlooked contributions of black people, particularly those who were enslaved, in shaping the modern world.

Dr Bulstrode emphasises the importance of recognising the true genesis of science and technological advancement. By acknowledging the contributions of marginalised communities, we gain a more comprehensive understanding of history and can work towards repairing the developmental opportunities denied to postcolonial states. This narrative also contributes to the discourse of technological transfer as a key aspect of the reparations movement.