Where is Haiti?

Haiti is in the western one-third of the island of Hispaniola between the Caribbean Sea and the North Atlantic Ocean. The Dominican Republic occupies the eastern two-thirds of the island. Port-au-Prince is the capital city of Haiti.

When was Haiti colonised?

Haiti was first colonised by the Spanish who enslaved the native Taino and Ciboney people soon after December 1492, when European navigator Christopher Columbus sighted the island and called it La Isla Española (“The Spanish Island”; later Anglicised as Hispaniola.) The island’s indigenous population, forced to mine for gold, devastated by European diseases and brutal working conditions, almost vanished by the end of the 16th century. Thousands of slaves imported from other Caribbean islands met the same fate.

Haiti under French rule

After the Spanish exhausted the main gold mines, the French established their own permanent settlements and renamed the colony Saint-Domingue succeeded.

Under French rule, Saint-Domingue grew to be the wealthiest colony in the French empire and, perhaps, the richest colony in the world, producing roughly 40 per cent of the sugar and 60 per cent of the coffee imported to Europe.

The colonial economy of Saint-Domingue was based almost entirely on the production of plantation crops for export. Enslaved Africans grew sugar and coffee.

To supply the plantation system, French owners imported almost 800,000 Africans to Saint-Domingue (which, by comparison, is almost double the number of Africans carried to North America). The slave system in the colony was regarded as one of the harshest in the Americas as French slave owners worked Africans brutally. There were high levels of both mortality and violence.

It is not surprising that Saint-Domingue was to prove fertile ground for the grievances of the enslaved, whose anger erupted with fury after the ideals and the turmoil of the French Revolution swept through French Caribbean colonies after 1789.

Haiti Revolts

The Haitian Revolution stands out as the only instance where enslaved people and free people of colour fought and defeated the French, Spanish, and British to end slavery and the slave trade. This successful and complicated campaign for freedom and equality began in 1791 and in 1803 Jean-Jacques Dessalines led the Haitian army against France, England, and Spain. Through the struggle, the Haitian people ultimately won independence from France and raised their own flag.

On 1 January 1804, the entire island was declared independent under the Arawak-derived name of Haiti. Haiti became the first country founded by former slaves.

Despite their hard one freedom, nearly the entire population was totally destitute—a legacy of slavery that has continued to have a profound impact on Haitian history.

France did not recognise Haiti’s independence until 1825, and then only in exchange for a large compensation of 150 million francs.

Newspaper articles from the period reveal that the French king, Charles the tenth knew the Haitian government couldn’t make these payments, as the total was over 10 times Haiti’s annual budget. The rest of the world seemed to agree that the amount was absurd. One British journalist noted that the “enormous price” constituted a “sum which few states in Europe could bear to sacrifice.”

But by complying with an ultimatum that amounted to extortion, Haiti gained immunity from French military invasion, relief from political and economic isolation – and crippling debt that took 122 years to pay off. The figure of 150 million francs was reduced to 90 million but still took until 1947 to pay off.

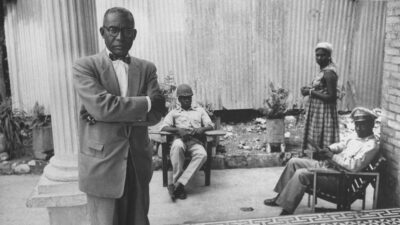

The Duvaliers

Haiti has had many rulers including the American occupation in 1915, but the ones that stand out the most in modern times are François Duvalier and his son Jean Claude.

François Duvalier, also known as “Papa Doc,” was elected president in September 1957.

Duvalier promised to end domination by the mulatto elite and to extend political and economic power to the black masses. Violence continued, however, and there was an unsuccessful attempt to overthrow Duvalier in July 1958. In response, Duvalier organised a paramilitary group, the so-called Tontons Macoutes, Haitian Creole for Bogeymen, to terrorise the population. In 1964 Duvalier. by then firmly in control, had himself elected president for life. Haiti under Duvalier was in effect a police state.

During Duvalier’s time in power, Haiti experienced increasing international isolation, renewed friction with the Dominican Republic, and a marked exodus of Haitian professionals. The regime was characterised by corruption and human rights abuses, but a personality cult developed around Duvalier himself, and some sectors of society strongly supported him, including a small upwardly mobile black middle class.

Near the end of his life, Duvalier faced a shrinking economy, withdrawal of most U.S aid, and a decline in tourism. In response, he relaxed some of the severe repression and terror that had been typical of his early regime.

When he died in 1971, his son, Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier aged, nineteen took over. There were no elections during either regime, and both presidents used force to keep the populace subservient.

Haiti today

There has been civil unrest in Haiti since July 2018 as protesters call for the resignation of President Jovenel Moise, amid anger over fuel and food shortages, a steep currency devaluation and corruption allegations.

At the heart of the fuel crisis is the collapse of the PetroCaribe program under which Venezuela, for a decade offered aid and cheap financing to several Caribbean nations to buy its gasoline, diesel and other products.

As opposition leaders call for the resignation of the president, Jovenel Moise, it is hoped that Haiti will one day get the strong, dedicated leaders it needs to improve the lives and conditions of the people.

Watch the video for a more indepth history of Haiti.