The Great Game stands as one of history’s most enduring geopolitical rivalries, a century-long strategic competition between the British and Russian Empires that shaped the destiny of Central Asia, Afghanistan, and the broader region between the 1830s and 1907. This term, popularised by British intelligence officer Arthur Conolly and later immortalised in Rudyard Kipling’s novel “Kim,” described a complex web of diplomatic manoeuvring, espionage, territorial expansion, and proxy conflicts that would define imperial politics in the 19th century.

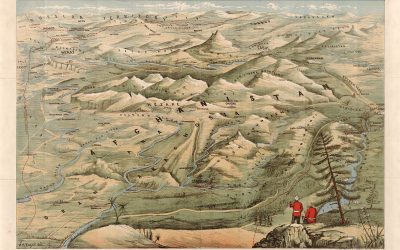

At its core, the Great Game represented a clash between two expanding empires: Britain, seeking to protect its crown jewel of India, and Russia, pursuing southward expansion toward warm-water ports and strategic positioning in Asia. The battleground was the vast, largely unmapped expanse of Central Asia, where ancient trade routes, tribal kingdoms, and emerging nation-states became pawns in a larger imperial chess match.

Historical context and origins

The roots of the Great Game can be traced to the early 19th century when both empires began expanding into territories that would eventually bring them into direct competition. Russia’s expansion into Central Asia accelerated following its conquest of Kazakhstan and gradual absorption of the Central Asian khanates. Meanwhile, Britain’s control over India, established through the East India Company, created an urgent need to secure the subcontinent’s northwestern frontier.

The catalyst for sustained rivalry emerged from Britain’s growing paranoia about Russian intentions toward India. British strategists, influenced by geopolitical theories and intelligence reports of varying reliability, became convinced that Russia harboured designs on British India. This fear was not entirely unfounded; Russian military manuals did discuss potential routes to India, and some Russian officials openly advocated for challenging British dominance in the region.

The first significant manifestation of this rivalry occurred during the First Anglo-Afghan War (1839-1842) when Britain attempted to install a friendly ruler in Kabul to create a buffer against potential Russian influence. The disastrous outcome of this intervention, culminating in the retreat from Kabul and the near-complete destruction of British forces, demonstrated the challenges both empires would face in attempting to control Afghanistan.

Key players and personalities

The Great Game produced a remarkable cast of characters whose exploits became legendary. On the British side, figures like Alexander Burnes, a Scottish explorer and diplomat who conducted extensive reconnaissance in Central Asia before his murder in Kabul, embodied the adventurous spirit of imperial intelligence gathering. Francis Younghusband, who led the controversial British expedition to Tibet in 1904, represented the more aggressive phase of British forward policy.

Russian players included Mikhail Chernyayev, known as the “Lion of Tashkent” for his conquest of Central Asian territories, and Konstantin Kaufman, the first Governor-General of Russian Turkestan, who systematically expanded Russian control throughout the region. These military commanders often acted with considerable autonomy, sometimes pursuing expansion beyond their government’s explicit instructions.

Perhaps most intriguing were the intelligence operatives and explorers who risked their lives gathering information in hostile territory. Characters like the British spy Captain Frederick Gustavus Burnaby, who made unauthorised journeys into Russian Central Asia, and Russian agents like Nikolai Przhevalsky, who conducted extensive explorations of Central Asia under the guise of scientific research, captured the imagination of their contemporaries and posterity alike.

Major conflicts and crises

Several critical episodes punctuated the Great Game, each escalating tensions and reshaping the strategic landscape. The Panjdeh Incident of 1885 brought Britain and Russia to the brink of war when Russian forces occupied the Afghan oasis of Panjdeh, challenging British influence in Afghanistan. Only diplomatic intervention prevented a direct military confrontation between the two empires.

The competition extended beyond Afghanistan into Tibet, where both powers sought influence over the Dalai Lama’s government in Lhasa. The British expedition to Tibet under Younghusband in 1904 was partly motivated by fears of Russian influence in the region, though these concerns proved largely exaggerated.

Throughout Central Asia, proxy conflicts and diplomatic chess moves characterised the rivalry. Russia systematically conquered the independent khanates of Khiva, Bukhara, and Kokand, while Britain responded by tightening its control over border regions and establishing protectorates over various Afghan tribes and territories.

Geographic scope and strategic importance

The Great Game encompassed a vast geographical area stretching from the Caspian Sea to the Hindu Kush, from the Siberian steppes to the Persian Gulf. This region’s strategic importance derived from several factors: it controlled traditional trade routes between Europe and Asia, offered potential access to warm-water ports for Russia, and served as a buffer zone protecting British India from potential northern invasion.

Afghanistan emerged as the primary focus of competition due to its position as a natural corridor between Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent. The country’s tribal structure and difficult terrain made it virtually impossible to control directly, yet both empires recognised that influence in Kabul could tip the regional balance of power.

The Pamirs, often referred to as “the Roof of the World,” became another crucial battleground where British and Russian survey teams competed to map territories and establish territorial claims. These high-altitude expeditions, conducted under extreme conditions, were just as much about imperial prestige as they were about strategic advantage.

Intelligence and espionage

The Great Game pioneered modern intelligence gathering and espionage techniques. Both empires developed sophisticated networks of agents, often operating undercover as merchants, scholars, or explorers. The British Survey of India conducted extensive mapping operations, creating detailed intelligence about potential invasion routes and strategic positions.

Russian intelligence operations were equally sophisticated, utilising the cover of scientific expeditions and commercial missions to gather strategic information. The quality and accuracy of intelligence varied considerably, leading to decisions based on incomplete or misleading information that sometimes escalated tensions unnecessarily.

The famous “Tournament of Shadows,” as the Russians called this intelligence competition, involved elaborate schemes of deception, counter-intelligence, and information warfare that would influence espionage practices well into the 20th century.

Economic dimensions

While strategic concerns dominated Great Game calculations, economic factors also played a significant role in driving imperial expansion. Russia’s conquest of Central Asia opened new markets for Russian manufactured goods and provided access to valuable cotton production, reducing dependence on American cotton supplies disrupted by the Civil War.

Britain’s economic interests focused primarily on protecting India’s markets and maintaining control over strategic trade routes. The potential for Russian interference with British commercial interests in Asia provided additional motivation for maintaining buffer zones and spheres of influence.

The construction of transportation infrastructure, particularly railways, became a central component of the Great Game strategy. Russia’s Trans-Caspian Railway enabled rapid deployment of troops and supplies to Central Asia, while British plans for railway construction in Afghanistan and frontier regions aimed to counter Russian advantages.

The end of the Great Game

The Great Game gradually wound down as both empires faced more pressing challenges elsewhere and recognised the limitations of their Central Asian ambitions. The Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907 formally delineated spheres of influence in Persia, Afghanistan, and Tibet, effectively ending the competition phase of the Great Game.

This agreement emerged from several factors: Russia’s defeat in the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905) and subsequent internal revolution reduced its capacity for Asian expansion; Britain’s growing concern about German naval power in Europe made Russian cooperation more valuable than continued competition in Asia; and both empires had reached practical limits of expansion in inhospitable Central Asian territories.

Legacy and historical significance

The Great Game’s legacy extends far beyond its immediate historical context. It established patterns of great power competition in Central Asia that would resurface during the Cold War and continue to influence contemporary geopolitics. The arbitrary borders and spheres of influence established during this period contributed to ongoing regional instability and conflict.

The rivalry also advanced geographical knowledge and exploration of Central Asia, resulting in detailed maps and a deeper scientific understanding of previously unknown regions. The intelligence gathering techniques and strategic thinking developed during the Great Game influenced military doctrine and diplomatic practice well into the modern era.

Perhaps most significantly, the Great Game demonstrated both the possibilities and limitations of imperial power projection in difficult terrain among resistant populations. The experiences of Britain and Russia in Afghanistan and Central Asia provided cautionary lessons about the challenges of controlling territory through military force alone.

Conclusion

The Great Game represents a fascinating chapter in the history of imperial competition, combining elements of adventure, strategic thinking, cultural encounters, and geopolitical rivalry. While neither empire achieved its maximum objectives in Central Asia, the competition shaped the region’s development and established enduring patterns of international relations.

The story of British and Russian rivalry in Central Asia offers valuable insights into the dynamics of great power competition, the role of geography in international relations, and the complex interplay between imperial ambitions and local realities. As contemporary powers again compete for influence in Central Asia and Afghanistan, the lessons of the Great Game remain remarkably relevant, reminding us that some strategic competitions transcend specific historical periods and continue to shape international relations across centuries.

The Great Game ultimately demonstrated that even the most powerful empires must reckon with the practical limits of their reach and the enduring influence of local conditions, terrain, and populations in determining the outcome of geopolitical competition.

Leave a Reply