Britain’s 1919 race riots started at the end of the First World War starting with an outbreak of violence in Glasgow in January, race riots happened around the United Kingdom until late in the summer, including in Liverpool, Hull, Cardiff, Salford, Newport and South Shields. There were several outbreaks in the East End of London, in Poplar and Canning Town and Limehouse.

Just as with the Notting Hill riots, these riots were in retaliation against the growing black communities.

British Black presence

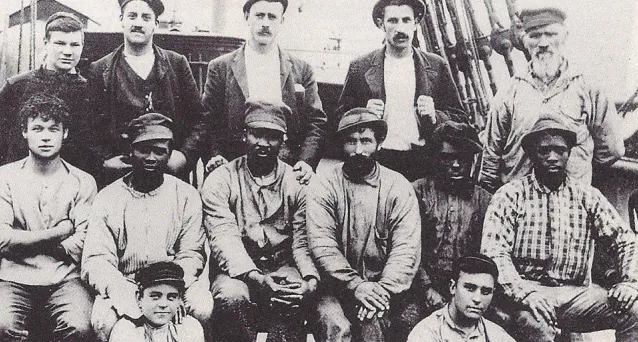

Since the 16th century, the black presence in London and Liverpool had been noticeable but ballooned following World War I when the nation entered a period of economic downturn.

Liverpool’s black population had grown dramatically during the war and welcomed by industries such as chemicals, sugar refining and munitions in order to fill the labour shortage created when white British workers enlisted in the armed forces.

Job shortages

At the end of the war in November 1918, the city’s population increased further when black servicemen were demobilised and black seafarers discharged to Liverpool. Estimates of the size of the population vary from 2,000 to 5,000. White servicemen returned from the front lines, hoping to continue their lives found that there were few jobs and too much competition.

This dissatisfaction among Britain’s white workers, particularly the sailors, led to resentment of the presence of black labour. Along with African, Afro-Caribbean, Chinese and Arab sailors, South Asians were targeted because of the highly competitive nature of the job market and the perception that these minorities were ‘stealing’ the jobs that should belong to white indigenous British workers. The housing shortage because of a lack of materials and labour during the war exacerbated the situation.

This was the key factor that led to the outbreak of race rioting in Britain’s major seaports from January to August 1919. Another significant factor, of course, was racism, and specifically the fear of interbreeding, which also motivated the hostility towards these settlers.

1919 race riots in Liverpool

As the war-time requirement for extra labour dried up, the subject of ‘aliens’ taking jobs and houses from white workers was raised within the House of Commons. Many businesses hired Indian seamen at a considerably lower rate than their white counterparts. Although workers had to tolerate poor working and living conditions, unions blamed them for undercutting the wages of white workers.

White workers refused to work alongside black workers and a colour bar, supported by trade unions, was imposed across Liverpool.

Black organisations and churches appealed to the Lord Mayor of Liverpool on behalf of black citizens. They detailed the destitution faced by those unable to return home and by those who had settled here, many with families and unable to seek out work.

The Lord Mayor also received a delegation claiming to represent 5,000 unemployed white ex-servicemen and seafarers complaining of competition from black workers, a situation with which he sympathised. By May 1919, as attacks on black men increased, the Lord Mayor was reporting outbreaks of violence to the Colonial Office and was seeking support in finding an answer to the problem of ‘coloured labour’.

On the evening of 5 June 1919, a fight broke out in Great Georges Square, Liverpool. The police were called and arrested the black men. The events that followed resulted in the murder of Charles Wotton.

Despite the death of Charles Wotton, the atrocities continued for several days. Crowds, several thousand strong, attacked black-occupied homes and hostels. Entire buildings were vandalised, emptied of their furniture and even set alight. Within a week the police, unable to cope, detained over seven hundred black residents in police stations for their own protection.

In the end, the super-dreadnought ship HMS Valiant and two escorts were called in to support the police to quell the riots.

Riots in Wales

The port towns of South Wales had attracted settlers from all over the world during the heyday of the docks in the latter decades of the 19th century. By 1911 the proportion of Cardiff’s population that was black or Asian was second in the UK to London though, at around 700, the number was quite small and confined to the dock areas. Wages in the docks were undercut by employing foreign men at a lower rate. The Cardiff Seaman’s Strike in June 1911 had become focused on Chinese sailors, with violence breaking out one afternoon resulting in all of Cardiff’s Chinese laundries being smashed up.

Labour shortage and shrinking industries in port areas such as Cardiff and Liverpool were widespread. White working-class union workers and former servicemen who lacked the resources to challenge shipping magnates, blamed, targeted, and took out their frustrations on blacks and other ethnic minorities who they saw as foreign competitors for jobs and for the attention of white women, thus threatening Britain’s post-war national identity.

By July 1919, 1,300 of Cardiff’s 2,000 registered unemployed were demobilised troops. “We went to France and when we came back foreigners have got our jobs and we can’t get rid of them,” complained one unemployed former soldier in Cardiff in July 1919. And it was in the docklands of south Wales – especially in Newport, Barry and the Welsh capital – that these grievances were to explode into violence in the early summer of 1919.

Newport

Rioting initially broke out in Newport on 6 June 1919. A white soldier attacked a black man, because of an alleged remark made to a white woman. This rapidly escalated, with a mob of white men attacking anyone perceived to be non-white, or anything believed to be owned by non-whites. Houses and a restaurant owned by black people, Chinese laundries and a Greek-owned lodging house were attacked in Pillgwenlly and the town centre. They wrecked eight houses in the docks area, with furniture from two of them being burnt in the street.

Cardiff

Clashes took place on 11 June 1919 between white soldiers and local Butetown men of mainly Yemeni, Somali and Afro-Caribbean backgrounds. Riots continued for three days, spreading out into Grangetown and parts of the city centre. Ethnic minority families armed themselves and hid in their houses, whilst the mob attacked and looted them.

The main road in Butetown, Bute Street, ended up covered with broken glass and the windows boarded up. By Saturday 14 June, things had quietened down, despite vast crowds being on the streets the day before, and the occupants of a Malay owned shop having to escape attack by climbing on to their roof.

Barry

Threatening crowds gathered in Barry on the evening of 11 June 1919, following a fatal stabbing in Beverley Street, Cadoxton. Charles Emmanuel, who originated from the French West Indies, had stabbed dock labourer, Frederick Longman. Longman told Emanuel to “go down your own street” and attacked him with a poker, so Emanuel drew his knife.

A black shipwright who lived in the same street tried to escape when the mob broke into his lodging house. The crowd caught up with him and pelted him with stones. The crowds didn’t disperse until after midnight.

Arrests and prosecution

Reports by local and national media placed the blame for the riots on black men, as did the police who arrested the Black victims of violence out of all proportion to their numbers, and relatively few white perpetrators. In nearly all cases, white crowds numbering in the hundreds and sometimes thousands made up the aggressors and Black men and their families the victims, yet nationally police arrested nearly twice as many Black men as white men and women. Some even prosecuted men of colour that had been taken into protective custody.

Despite the blatant racism, the courts acquitted nearly half of Black arrestees. It seems the courts recognised and attempted to correct police bias. In contrast, white perpetrators of either sex were overwhelmingly convicted. Sentences of those Black men and white women convicted proved harsher than those of white men for equivalent crimes. The courts, while less racist than the police, still clearly practised institutional racism and sexism.