Spain built one of history’s most ambitious empires in a matter of decades, but ambition alone doesn’t extract silver from mountains or sugar from fields. For that, you need labour. Enormous quantities of it. And in the late fifteenth century, Spain found a solution that was elegant in its cynicism: dress exploitation up as Christian charity, hand it a legal framework, and call it protection.

That solution was the encomienda. It would go on to reshape entire civilisations, kill millions, and plant the seeds of inequality that Latin America is still reckoning with today.

A system built on a lie

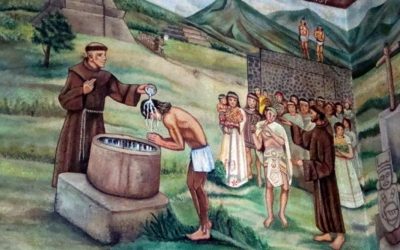

The word encomienda comes from encomendar, “to entrust.” The Spanish Crown would entrust Indigenous communities to a colonist called an encomendero, who was officially responsible for their protection, their governance, and their conversion to Christianity. In exchange, those communities owed him tribute and labour.

On paper, it almost sounded reasonable. In practice, it was a machinery of coercion.

Forced labour in mines and on plantations. Punishing quotas that couldn’t be met. Brutal discipline for those who fell short. The Crown insisted that Indigenous people were “free vassals,” not slaves, but this distinction evaporated the moment someone was dragged into a silver mine at altitude and told not to come back until his quota was filled.

Many historians describe the encomienda as feudalism exported to the Americas. That’s accurate, as far as it goes, but it undersells the racial dimension. This wasn’t just hierarchy. It was a hierarchy written in skin.

The Caribbean: Where it began

The system took its first steps on Hispaniola, the island Columbus settled in the 1490s that today holds Haiti and the Dominican Republic. The Taíno people were its first victims, put to work mining gold, farming for Spanish settlements, and building the colonial infrastructure that would make further conquest possible.

The results were catastrophic. Within decades, a Taíno population once numbering in the hundreds of thousands had been reduced to a few thousand survivors — ground down by disease, overwork, and violence in one of the most rapid demographic collapses in recorded history.

The Caribbean was Spain’s testing ground. Once the system proved profitable, it followed the conquistadors wherever they marched.

Mexico and Peru: Exploitation at scale

When Hernán Cortés dismantled the Aztec Empire in 1521, the encomienda came with him. Conquistadors received entire towns as rewards for their service, and the dense, well-organised populations of central Mexico — who had already been paying tribute to Aztec rulers — simply found themselves paying it to Spanish ones instead. The extraction infrastructure was already in place. The Spanish just changed who sat at the top.

In Peru, Francisco Pizarro did the same after defeating the Inca Empire, but with a particularly brutal twist: the Spanish merged the encomienda with the Inca mita, a traditional labour draft, and turned it into something darker than either had been on its own. Nowhere was this more visible than in the silver mines of Potosí, high in the Andes, where Indigenous workers died by the thousands from mercury poisoning, tunnel collapses, and sheer exhaustion. The wealth that poured out of those mountains financed Spain’s wars, its art, and its global ambitions. The people who dug it out rarely lived to see old age.

The system also took root in Guatemala, Colombia, Venezuela, and even the early Philippines — wherever Spain found dense populations, it could organise into a workforce.

The men it made rich, and the man who fought back

The primary beneficiaries were the conquistadors themselves, men who had taken enormous risks in conquest and expected to be paid, not in coin, but in people. Colonial elites built their fortunes on encomienda labour, and the Spanish Crown, though it never got its hands dirty, collected taxes on the whole enterprise and used it to bind powerful colonists to the empire’s interests.

But the brutality was hard to ignore even at the time. The most powerful voice against it belonged to Bartolomé de las Casas, a Dominican friar who had seen the suffering firsthand and spent decades arguing that the system was not just cruel but a theological catastrophe — a betrayal of everything Christianity claimed to stand for.

His campaign helped produce the New Laws of 1542, which aimed to end the worst abuses, strip encomiendas of their hereditary status, and eventually phase the system out entirely.

The colonists responded with open revolt. In Peru, the resistance nearly brought down Spanish rule altogether. Faced with losing the empire, the Crown backed down. Enforcement weakened, exceptions multiplied, and the encomienda didn’t so much end as transform — bleeding slowly into debt peonage, into the hacienda system, into new arrangements that preserved the essential relationship between coerced brown labour and enriched white landowners.

The name changed. The exploitation didn’t.

What it left behind

The encomienda’s consequences didn’t end when the system did. They compounded.

The demographic collapse it accelerated, disease magnified by brutal working conditions, killed millions of Indigenous people and permanently altered the population of an entire continent. The racial hierarchy it institutionalised, with Spaniards at the apex and Indigenous people at the base, hardened into the caste systems that structured colonial society for centuries. The concentration of land and wealth in elite hands created patterns of inequality so entrenched that economists and historians still trace today’s disparities back to this period.

And when Indigenous populations fell too sharply to sustain the labour demand, colonists turned to Africa. The encomienda didn’t create the Atlantic slave trade, but it created the appetite for it.

The bottom line

The encomienda was one of history’s first large-scale systems of colonial labour extraction, and it worked precisely because it never called itself what it was. Framed as civilisation, operated as coercion, defended as Christian duty — it allowed a small class of Spanish colonists to accumulate staggering wealth at a human cost that beggars description.

It wasn’t slavery in name. For the millions who lived and died under it, that distinction meant nothing at all.

If you want to understand where Latin America’s inequalities come from — the land concentration, the racial fault lines, the legacy of extraction over investment — you have to start here. Almost every thread, eventually, leads back to the encomienda.

Leave a Reply