You’ve heard of Rosa Parks, but what do you know of Claudette Colvin? Nine months before Rosa Parks refused to move to the back of a bus in Montgomery, Alabama, 15-year-old Claudette did the exact same thing.

Early life

Claudette Austin was born in Birmingham, Jefferson County, to Mary Jane Gadson and C P Austin on 5 September 1939. Her father abandoned the family when she was a small child. Claudette and her sister went to live in Pine Level, Montgomery County, with an aunt and uncle, Mary Anne and Q P Colvin. Both children took the Colvin name as their last name at this time. When Colvin was eight, the family moved to Montgomery. There Claudette became a student at the segregated Booker T Washington High School.

1955 as during Negro History Month, the children had been studying Black leaders such as Harriet Tubman, the runaway slave who led many slaves to freedom through the Underground Railroad. They also learned about Sojourner Truth, a former slave who became an abolitionist and women’s rights activist.

Claudette became a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) Youth Council and had aspirations to become a civil rights attorney. There she formed a close relationship with her mentor, Rosa Parks.

The Youth Councils were founded in 1935 with the goal of training the next generation of civil rights activists and included chapters for junior high, high school, and college students.

Montgomery bus incident

On 2 March 1955, Claudette and her friends finished their classes and were let out of school early. They got on the bus and sat in the middle. Segregation laws dictated that white people got to sit at the front of the bus and Black people sat at the back. If the bus was full, the bus driver had the authority to ask the Black people to stand up and give their seats to a white person.

That is what happened on that day. Colvin and her friends were sitting in a row a little more than halfway down the bus – two were on the right side of the bus and two on the left – and a white passenger was standing in the aisle between them.

The driver wanted all of them to move to the back and stand so that the white passenger could sit. Three of the students got up, but Claudette remained seated in her window seat. Under segregation laws, this was not good enough, as white and Black passengers could not share a row of seats.

Arrested

Claudette told the driver she had paid her fare and that it was her constitutional right to remain where she was. The driver kept on driving but stopped when he reached a junction where a police squad car was waiting. Two policemen boarded the bus and asked Colvin why she wouldn’t give up her seat.

They dragged her from the bus whilst Colvin shouted repeatedly: “It’s my constitutional right.” Colvin was handcuffed and taken to jail. Instead of being taken to a juvenile detention centre, she was taken to an adult jail and put in a small cell with nothing in it but a broken sink and a cot without a mattress.

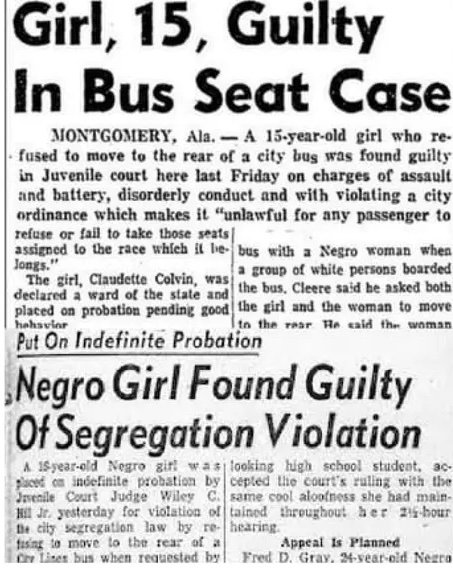

Claudette was charged with violating segregation laws, disturbing the peace and assaulting a police officer. She pleaded not guilty but was convicted.

In Montgomery, there were several women who refused to give up their seats to white people on the same bus system. Those women were fined, and their stories were never told, but Claudette Colvin was the first to really challenge the law. Her story made a few local papers.

The fact is the actions that Colvin took planted the seed for the Montgomery Bus Boycott later that year and provided the legal foundations to challenge transportation segregation laws in federal court.

Face of the movement wanted

Colvin’s plight caught the attention of local Black leaders, who helped secure legal representation. When Colvin’s case was appealed to the Montgomery Circuit Court on 6 May 1955, the charges of disturbing the peace and violating the segregation laws were dropped, although her conviction for assaulting a police officer was upheld.

The leaders thought about using her example as a symbol for a city-wide bus boycott but felt that she was too young to function as the rallying figure for what was certain to be an intense movement. When Colvin became pregnant for an older man later that summer, it presumably confirmed the sentiment that she was the wrong person for the moment.

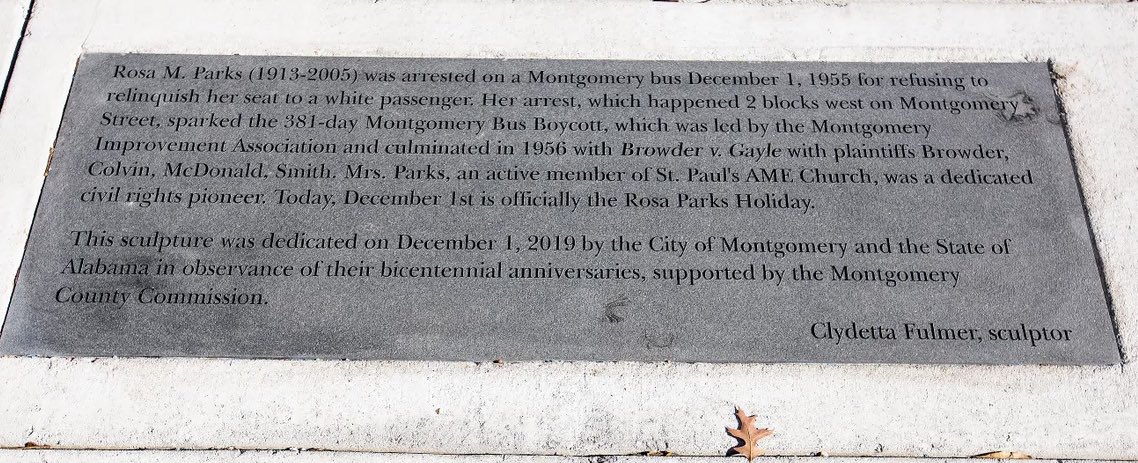

Nine months after Claudette Colvin refused to give up her seat, Rosa Parks became the “right person” on 1 December.

On the night of Parks’ arrest, the Women’s Political Council (WPC), a group of Black women working for civil rights, began circulating flyers calling for a boycott of the bus system. Soon afterwards, on 5 December, 40,000 Black bus passengers boycotted the system, and that afternoon, Black leaders met to form the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA), electing a young pastor, Martin Luther King Jr, as their president.

Lawsuit – Browder v. Gayle

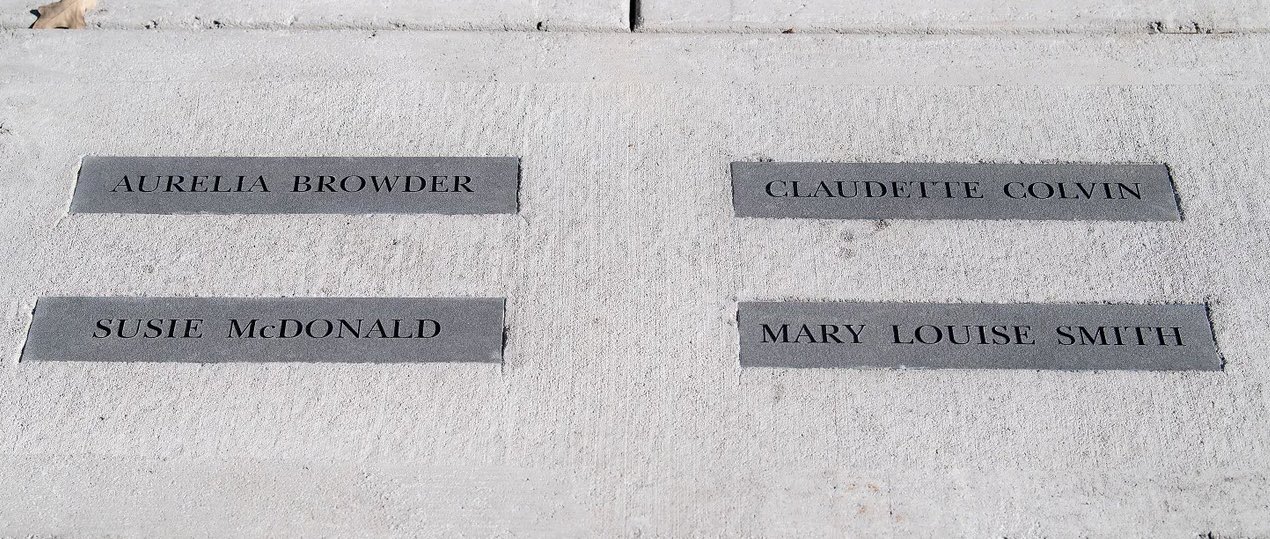

In early 1957, the NAACP asked Colvin to join a lawsuit alongside four other women who experienced similar mistreatment on a bus. They were Susie McDonald, Aurelia Browder, Mary Louise Smith and Jeanetta Reese. The four were named plaintiffs in Browder v. Gayle, a federal lawsuit that challenged the constitutionality of Montgomery’s segregation laws. Jeanetta Reese later resigned from the case.

Browder v. Gayle went all the way to the Supreme Court, where the justices found that Montgomery’s bus segregation was in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. This was a significant civil rights victory, and yet history forgot the part Claudette Colvin played until she and her family decided to fight for recognition in the early 2000s.

Recognition for Claudette Colvin

In 2017, the city of Montgomery, Alabama, declared 2 March Claudette Colvin Day.

In 2019 a statue of Rosa Parks was unveiled in Montgomery, Alabama, and four granite markers were also unveiled near the statue on the same day to honour Colvin and the three other plaintiffs in Browder v. Gayle.