A history of conquest, slavery, rebellion and the long struggle for freedom

The First Peoples: Before Columbus

Long before a European sail broke the Caribbean horizon, Cuba was home to several distinct indigenous peoples whose civilisations stretched back thousands of years. The oldest inhabitants were the Guanahatabey, a hunter-gatherer people who occupied the westernmost tip of the island and whose origins remain debated by archaeologists. They lived in caves and along coastlines, surviving on fish, shellfish, and whatever the forest provided. They left little in the way of constructed settlements, and much of what we know of them comes from the accounts of later arrivals who found them already in retreat.

By the time of Spanish contact, two other groups dominated the island. The Ciboney were a pre-agricultural people scattered across the western and central regions, living in relative simplicity compared to their neighbours. Far more numerous and culturally sophisticated were the Taino, an Arawakan-speaking people who had migrated northward through the Caribbean island chain from South America over centuries of maritime expansion. The Taino had established permanent villages, practised agriculture growing yuca (cassava), maize, sweet potatoes, and tobacco, and had developed a rich spiritual life centred on zemis, sacred objects believed to hold supernatural power. They organised their society around a chieftain system known as cacicazgos, with local chiefs called caciques governing communities that could number in the thousands.

It is estimated that between 100,000 and 500,000 indigenous people inhabited Cuba when Christopher Columbus made landfall on the island’s northeastern coast in October 1492, describing it in his journals as the most beautiful land human eyes had ever seen. Within a century, that entire population had been virtually annihilated.

The Spanish Conquest: Colonisation and catastrophe

Columbus claimed Cuba for the Spanish Crown and returned to Europe, but it was Diego Velázquez de Cuellar who carried out the systematic conquest of the island between 1511 and 1514. Setting out from Hispaniola with a force of several hundred soldiers, Velázquez subdued the island’s indigenous population through a campaign of sustained violence. The most famous act of resistance came from a Taino chief named Hatuey, who had fled to Cuba from Hispaniola to warn its people of what the Spanish intended. He organised guerrilla resistance in the eastern mountains, but was eventually captured. When a Franciscan friar offered him the chance to accept Christianity and ascend to heaven before his execution by fire, Hatuey reportedly asked whether Spaniards went to heaven. When told that good ones did, he replied he would rather go to hell. He was burned at the stake in 1512. His story became one of the founding myths of Cuban resistance.

Velázquez established the first Spanish settlements, including Baracoa, Santiago de Cuba, and most significantly, Havana, which by the mid-sixteenth century had become one of the most strategically important ports in the entire Atlantic world, a staging post for treasure fleets carrying gold and silver from the Americas back to Spain.

The colonisers introduced the encomienda system, a legal arrangement that in practice was indistinguishable from slavery. Under encomienda, Spanish settlers were granted a number of indigenous people whom they were technically obligated to protect and convert to Christianity; in return, those people owed their encomendero labour and tribute. In reality, the indigenous Cubans were worked to exhaustion in gold mines and on agricultural estates. The encomienda system was rationalised by the fiction that the Spanish were civilising and saving souls, but its economic logic was simple: the extraction of maximum labour at zero cost.

Disease, death and the destruction of a people

Violence alone did not destroy Cuba’s indigenous population, though violence was pervasive and brutal. What completed the catastrophe was biological. The Spanish brought with them diseases to which the Taino and other peoples had no prior exposure and therefore no immunity: smallpox, measles, typhus, influenza, and a host of other infections swept through indigenous communities with devastating speed.

The demographic collapse was staggering. Within fifty years of Columbus’s arrival, the indigenous population of Cuba had been reduced to a few thousand individuals. By the end of the sixteenth century, it had effectively ceased to exist as a coherent social force. The people who had farmed the island, named its rivers and mountains, and built its spiritual culture were gone. Some intermarried with Spanish settlers or enslaved Africans, leaving genetic traces that persist in the Cuban population today. But as distinct peoples, the Taino and their neighbours had been erased.

The Dominican friar Bartolome de las Casas, who had himself participated in the conquest of Cuba before experiencing a moral conversion, became the most prominent critic of Spanish treatment of indigenous people. His writings, including the searing ‘A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies‘ (1542), documented atrocities in horrifying detail and sparked what became known as the ‘Black Legend’ of Spanish colonial brutality. Las Casas’s advocacy contributed to the New Laws of 1542, which attempted to reform the encomienda system and eventually abolish indigenous slavery, though enforcement in distant colonies was inconsistent and often ignored.

The slave trade: Africa remakes Cuba

With the indigenous labour force destroyed, the Spanish colonisers turned to Africa. The transatlantic slave trade to Cuba began in earnest in the early sixteenth century and would continue, in various forms, until 1867. Over that period, an estimated 800,000 Africans were forcibly transported to Cuba — one of the largest slave importations in the entire Caribbean. They came primarily from West and Central Africa: Yoruba people (known in Cuba as Lucumi), Fon, Ewe, Congolese, and many others, each bringing with them languages, religious traditions, musical forms, and social structures that would permanently shape Cuban culture.

The sugar revolution of the late eighteenth century transformed the island’s economy and massively accelerated the demand for enslaved labour. When the Haitian Revolution of 1791 destroyed the world’s most productive sugar colony and sent its planter class fleeing, Cuba stepped into the resulting power vacuum. The island’s sugar output exploded. By the 1820s, Cuba had become the world’s leading sugar producer, and its plantations consumed enslaved lives at a terrifying rate. The mortality rate in the sugar mills was so high that planters calculated it was cheaper to work an enslaved person to death within a few years and purchase a replacement than to invest in conditions that might have prolonged their lives.

The brutality of the plantation system shaped Cuban society in lasting ways. Cuba’s enslaved population developed elaborate systems of cultural survival: Santeria, the syncretic religion that fused Yoruba orishas with Catholic saints, became a form of spiritual resistance. Mutual aid societies called cabildos allowed African-born Cubans to maintain communal bonds and preserve cultural memory. Music — the drumming rhythms that would eventually give birth to son, rumba, and mambo — became a language of solidarity and identity that crossed racial lines.

Abolition came late and unevenly to Cuba. Britain, which had abolished its own slave trade in 1807 and slavery itself in 1833, pressured Spain to end the trade, but Spanish and Cuban planters resisted fiercely. The trade was formally outlawed in 1820 but continued illegally for decades. Slavery itself was not abolished in Cuba until 1886 — the second to last country in the Western Hemisphere to do so, just two years before Brazil.

The Ten Years’ War: Cuba’s first revolution

By the middle of the nineteenth century, Cuban creole society — those born on the island of Spanish descent — had developed a distinct sense of identity and a growing resentment of Spanish economic and political control. Spain treated Cuba as a cash cow, imposing heavy tariffs, excluding Cubans from positions of political power, and resisting all calls for reform. The discontent that had been building for decades finally erupted on 10 October 1868, when a wealthy sugar planter and lawyer named Carlos Manuel de Cespedes freed the enslaved people on his estate, La Demajagua, and called them to join a rebellion against Spanish rule. His proclamation, known as the Grito de Yara, launched the Ten Years’ War.

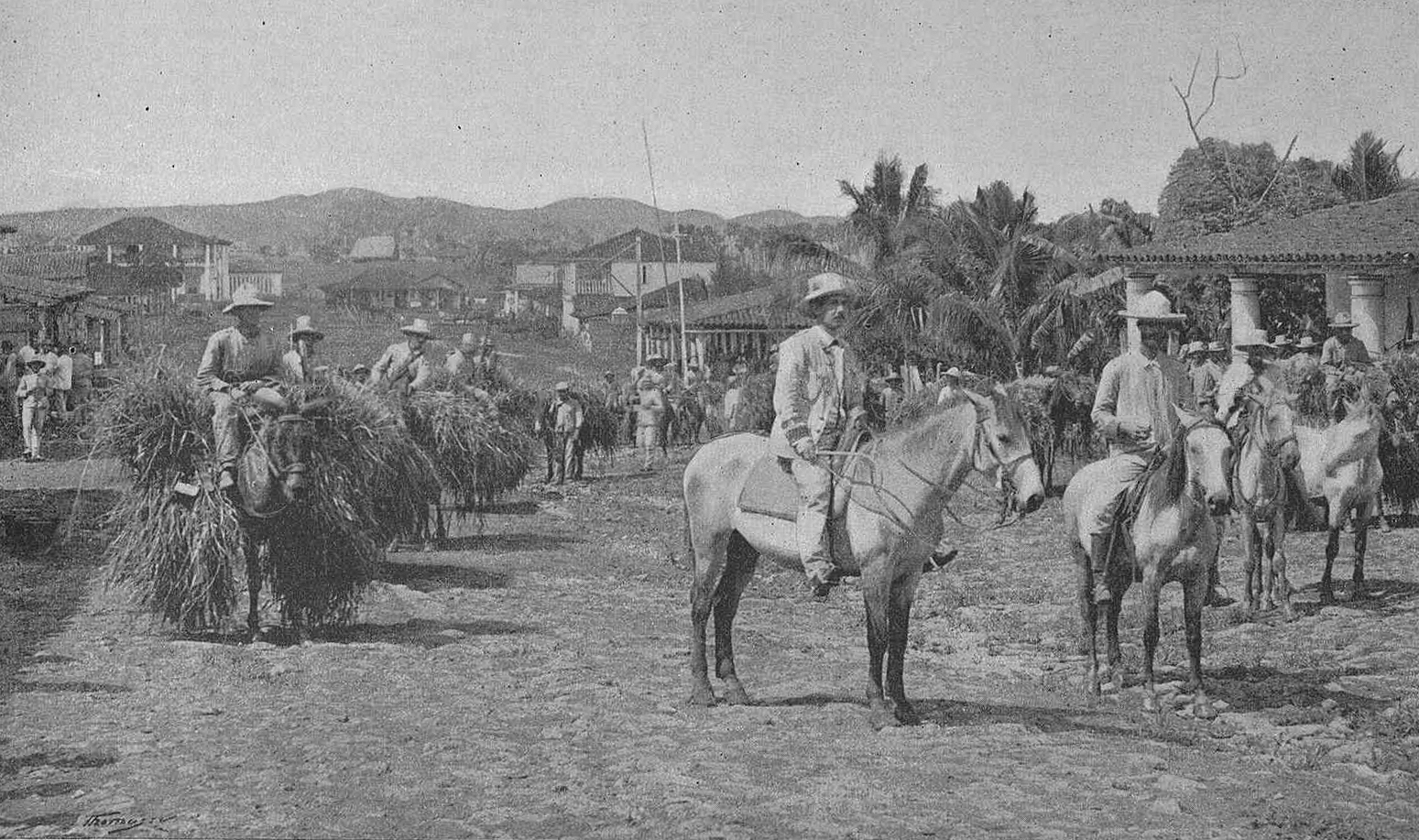

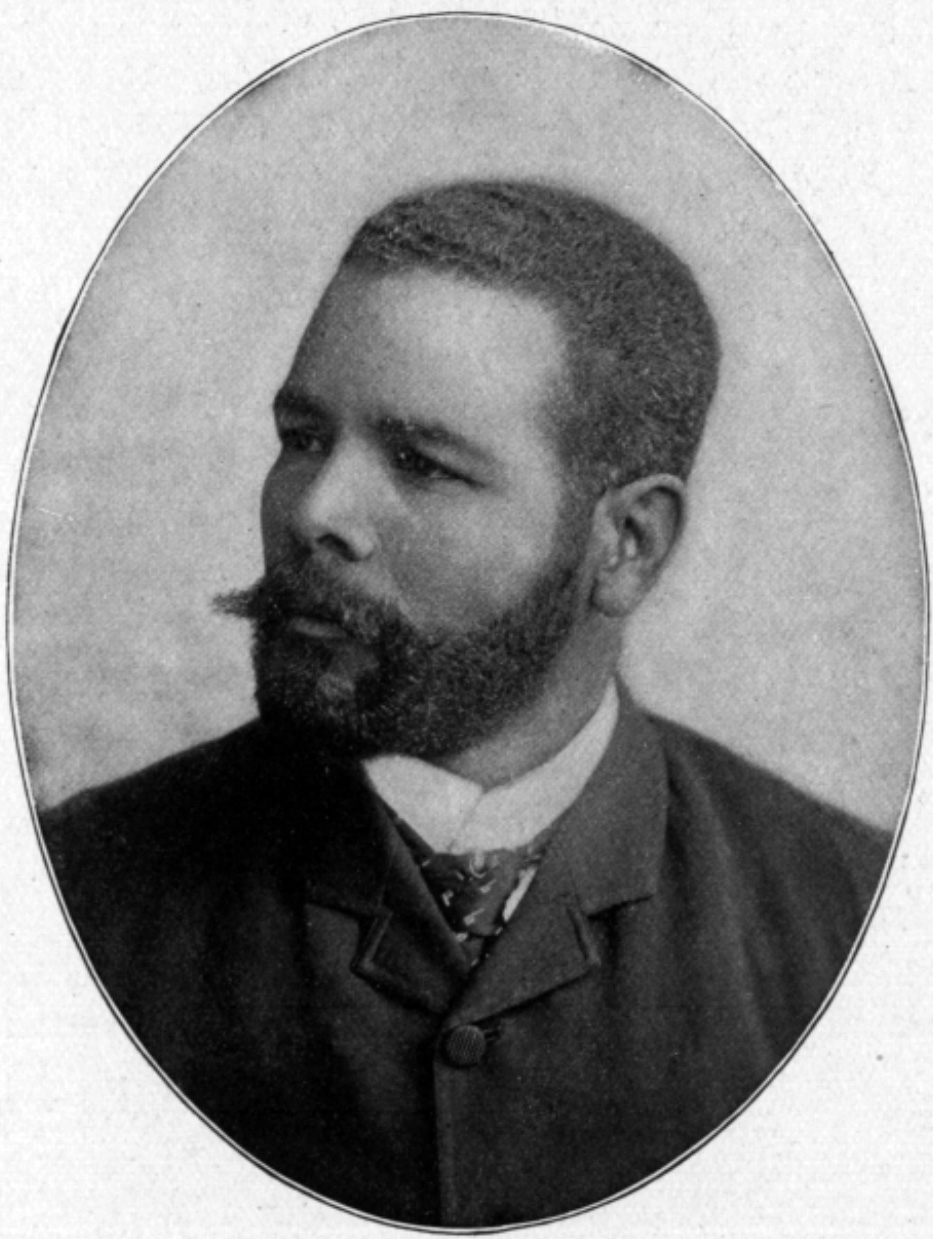

The conflict was a brutal, grinding insurgency. The Cuban Liberation Army, known as the Mambises, fought a guerrilla campaign across the eastern provinces, repeatedly engaging and frustrating the far larger and better-equipped Spanish forces. Cespedes was joined by a remarkable coalition that cut across the racial lines that had always defined Cuban society: free Black Cubans, formerly enslaved men, mixed-race officers and white Creole landowners fought together under the same banner. Among the most celebrated commanders was Antonio Maceo, the son of a Venezuelan immigrant and an Afro-Cuban mother, whose tactical brilliance and personal courage earned him the title ‘The Bronze Titan.’

The war ended in a stalemate. The Pact of Zanjon in 1878 offered amnesty, some political reforms, and the freedom of enslaved people who had fought in the rebellion, but it did not deliver independence. Maceo famously refused to accept the pact, issuing the Protest of Baragua, a ringing declaration that no peace was acceptable without full independence and the abolition of slavery. Though ultimately forced to go into exile, his protest became a defining symbol of uncompromising Cuban patriotism.

The ten years of war had left Cuba economically devastated and politically transformed. The old planter class had been weakened. Slavery was moving toward its end. And a generation of Cuban men had learned to fight.

José Martí and the war for independence

The figure who more than any other would define the Cuban independence movement in its final phase was not a general but a poet. Jose Marti was born in Havana in 1853 to Spanish immigrant parents, and from his teenage years showed a political consciousness that alarmed the colonial authorities. Arrested at sixteen for sedition, sentenced to hard labour, and eventually exiled to Spain, Marti spent the following decades living in exile across the Caribbean, Central America, and the United States, writing poetry, journalism, and political essays that galvanised the independence movement.

Marti was not merely a romantic nationalist. He developed a sophisticated and far-sighted vision of what independent Cuba should become: a racially inclusive republic that would repudiate the hierarchies of the colonial order. He was deeply wary of the United States, warning in his final letter, written the day before his death, that he had lived inside the monster and knew its entrails — and that American expansionism posed as great a threat to Cuba as Spanish colonialism. His writings warned against replacing one form of domination with another.

In 1892, Marti founded the Cuban Revolutionary Party and began organising the uprising that would become the final war for independence. He coordinated with veterans of the Ten Years’ War, including the ageing but still formidable Maximo Gomez and the indefatigable Antonio Maceo. On 24 February 1895, coordinated uprisings broke out across the island. Marti himself landed in Cuba in April, determined not to be a general who directed others from safety. He was killed in a skirmish at Dos Rios on 19 May 1895, just weeks after arriving. He was forty-two years old.

His death transformed him instantly into a martyr, but the war he had organised continued without him. Gomez and Maceo drove their forces westward in a devastating military campaign, burning sugar plantations to destroy the economic base of Spanish power. Spain responded by sending General Valeriano Weyler, whose policy of reconcentracion forcibly relocated hundreds of thousands of Cuban civilians into fortified towns, where tens of thousands died of disease and starvation. The brutality of Spanish tactics drew international condemnation, particularly in the United States, where a sensationalist press led by William Randolph Hearst whipped up public outrage.

The Platt Amendment: Independence in name only

The entry of the United States into the conflict in 1898, following the mysterious explosion of the USS Maine in Havana harbour, brought the Spanish-American War, which ended Spanish colonial rule in Cuba within months. Spain surrendered in August 1898. What followed, however, was not the independent Cuba that Marti had envisioned and the Mambises had bled for. Instead, it was American military occupation.

The United States governed Cuba from 1898 to 1902, and when it finally agreed to withdraw its forces and allow the establishment of a Cuban republic, it did so on terms that made a mockery of sovereignty. The Platt Amendment, written by US Senator Orville Platt and appended to an Army appropriations bill in 1901, was effectively imposed on Cuba’s constitutional convention as a condition of independence. Its most consequential provisions were stark: Cuba could not enter into any treaty with a foreign power that might impair its independence or allow colonisation of its territory by any other foreign power; Cuba could not contract any public debt beyond a certain limit; and, most significantly, the United States reserved the right to intervene in Cuban affairs to preserve Cuban independence, maintain a government adequate for protecting life, property and individual liberty, and to discharge the obligations imposed by the Treaty of Paris.

In practical terms, the Platt Amendment gave the United States a legal pretext to intervene in Cuba whenever it judged its interests to be threatened. American forces occupied the island again between 1906 and 1909, in 1912, and from 1917 to 1922. American corporations acquired vast tracts of Cuban land, particularly in the sugar and tobacco industries. The Guantanamo Bay naval base — established under the terms of a lease treaty that the Platt Amendment made possible — endures to this day as a physical reminder of that coerced arrangement.

Cubans were acutely aware of what the amendment represented. For the veterans of the independence wars and for Marti’s intellectual heirs, it was a betrayal of everything they had fought for. A revolution that had succeeded militarily and failed politically. The anger generated by the Platt Amendment would fuel Cuban nationalist politics for decades, eventually feeding into the revolutionary tradition that culminated in 1959. The amendment was finally abrogated in 1934 as part of Franklin Roosevelt’s Good Neighbour Policy, but the military lease on Guantanamo was kept in place and remains contested to this day.

Cuba’s story from colonisation to its compromised independence is, ultimately, a story about who gets to define freedom and for whose benefit. The Taino died before they could answer that question. The enslaved Africans who rebuilt the island answered it with resistance and cultural survival. The Mambises answered it with decades of warfare. Marti answered it with words that outlasted his short life. And the Platt Amendment demonstrated that even when a people wins the war, the victors of empire have ways of ensuring that freedom arrives with chains still attached.

Leave a Reply