A country on the brink

By the dawn of the twentieth century, Mexico had endured three decades under the iron hand of Porfirio Díaz. His regime, known as the Porfiriato, had modernised the country on the surface, threading it with railways, attracting foreign capital, and cultivating a veneer of stability that impressed European chancelleries and American investors alike. Beneath that surface, however, Mexico was a pressure cooker.

Land, the fundamental currency of life for millions of Mexicans, had been systematically stripped from indigenous communities and small farmers through the application of laws designed to “rationalise” rural property. By 1910, fewer than one per cent of the population controlled roughly ninety-seven per cent of the land. Vast haciendas stretched across Morelos, Chihuahua, and Oaxaca, worked by labourers trapped in cycles of debt bondage that were, in practice, indistinguishable from servitude. Díaz’s technocratic inner circle preached positivism and progress while presiding over a system of almost medieval inequality.

The urban working class fared little better. Strikes at the Cananea copper mine in 1906 and the Río Blanco textile mills in 1907 were crushed with brutal efficiency, becoming martyrs’ moments that radicalised a generation. Meanwhile, a growing middle class, lawyers, journalists, and small businessmen found political advancement blocked by a gerontocracy that had long since hollowed out elections into a pantomime.

When Díaz told an American journalist in 1908 that Mexico was “ready for democracy” and that he would not seek another term, the statement lit a fuse.

The spark: Francisco Madero and the fracture of the Porfiriato

Francisco Ignacio Madero was an unlikely revolutionary. A slight, earnest hacienda heir from Coahuila, he was a spiritualist and vegetarian who possessed a fierce moral clarity about political liberty. His 1910 book La sucesión presidencial called for genuine democratic reform and no re-election, a slogan that reverberated across a country hungry for change. When Díaz had him jailed and then rigged the election yet again, Madero issued the Plan de San Luis Potosí from exile in Texas following his escape from jail. The document called for a national uprising on 20 November 1910.

The date is now Mexico’s Revolution Day.

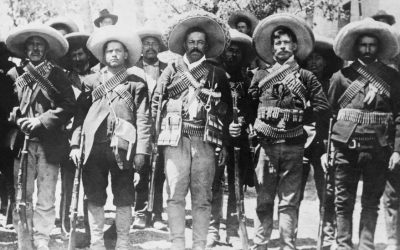

What followed was not a single, clean uprising but a kaleidoscope of regional rebellions that shared little beyond contempt for the old order. In Chihuahua, the cattle rustler turned military genius, Pancho Villa, assembled a Division of the North that would eventually command tens of thousands of men. In Morelos, Emiliano Zapata, a village leader of quiet intensity, rose in defence of his community’s stolen lands, issuing the Plan de Ayala with its elemental demand: Tierra y Libertad — Land and Liberty.

Díaz, watching his army dissolve and his allies scramble, resigned in May 1911 and sailed into exile in Europe. Madero entered Mexico City to rapturous crowds. The revolution, many thought, was over. It had barely begun.

Ten years of fire

Madero’s tragedy was that he was too democratic for his moment. He inherited Díaz’s generals but not Díaz’s ruthlessness, and he could not satisfy a country whose grievances ran far deeper than a change of president. Zapata broke with him within months, furious that land reform remained nothing more than words on paper. In February 1913, a conspiracy involving the United States ambassador Henry Lane Wilson and Díaz’s former general Victoriano Huerta ended in what Mexicans call the Decena Trágica — ten tragic days of urban fighting — and Madero’s murder. Huerta installed himself as dictator.

The assassination united Mexico’s fractured opposition in outrage. Venustiano Carranza, the governor of Coahuila, organised the Constitutionalist Army. Pancho Villa joined the cause. Álvaro Obregón, a former chickpea farmer from Sonora with a preternatural gift for military strategy, became perhaps the revolution’s most capable general. By mid-1914, Huerta was finished. American forces had seized Veracruz; Constitutionalist armies converged on the capital; Huerta fled.

What followed was arguably the revolution’s most genuinely radical moment: the Convention of Aguascalientes, where Villistas and Zapatistas briefly held power together, issuing programs for land redistribution that the more conservative Carranza could never accept. Civil war erupted again, this time among the victors. Obregón defeated Villa in a series of devastating set-piece battles in 1915 — the Battle of Celaya, where Obregón read the lessons of the Western Front and used barbed wire and machine guns to annihilate Villa’s cavalry charges, ending Villa’s capacity as a conventional military force.

Villa’s famous 1916 raid on Columbus, New Mexico, the first attack on US soil since 1812, prompted the United States to send General Pershing’s Punitive Expedition deep into Chihuahua. They never caught Villa. He fought on until 1920, a guerrilla ghost in his own mountains.

Zapata held out in Morelos until April 1919, when he was lured into an ambush by a Carrancista colonel at the Hacienda de Chinameca and shot. His followers refused for years to believe he was dead. The mountains, they said, kept him.

Carranza himself was overthrown and killed in 1920 by Obregón, who became president and whose political settlement, consolidated by his successor Plutarco Elías Calles, finally closed the decade of armed conflict.

The Constitution of 1917

Before the killing was done, Carranza convened a constitutional convention at Querétaro in late 1916. The delegates he expected to produce a modest liberal document surprised him. Radical delegates, many of them labour organisers and veterans who had watched men die for land and dignity, pushed through provisions that were startling for their time.

Article 27 subordinated all private property to the social interest, vesting ultimate ownership of subsoil resources in the nation and providing the legal framework for land redistribution. Article 123 enshrined labour rights: the eight-hour day, the right to strike, minimum wages, and protections for women and children. Article 3 established secular public education. The Constitution of 1917 remains, amended but fundamentally intact, the law of Mexico today, a document that encoded revolutionary aspiration into the structure of the state.

Legacy: The long afterlife of the revolution

The revolution’s immediate human cost was staggering. Estimates of the dead range from 500,000 to two million, out of a population of roughly fifteen million. Entire regions were depopulated; agricultural production collapsed; epidemic disease followed the armies. Mexico in 1920 was exhausted, scarred, and uncertain about what it had won.

What it had won, it turned out, was enormous, though it arrived slowly and unevenly.

Land reform, fitful under Obregón and Calles, became a mass reality under Lázaro Cárdenas in the 1930s, who distributed nearly twenty million hectares of land to peasant communities and nationalised the foreign-owned oil industry in 1938, a moment of national catharsis that Mexicans still commemorate every 18 March. The ejido, a form of communal landholding, became a defining feature of rural Mexico for most of the twentieth century.

The revolution also produced a cultural efflorescence of rare intensity. The muralists Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros covered the walls of government buildings with epic frescoes that reimagined Mexican history from the bottom up, celebrating indigenous roots and revolutionary heroes while indicting the Church, the landowner, and foreign capital. The revolution gave Mexico a usable past and a nationalist mythology, sometimes tendentious, sometimes genuinely inspired, that shaped the country’s identity for generations.

Politically, the revolution’s legacy was more ambiguous. The Institutional Revolutionary Party (the PRI) governed Mexico for seventy-one unbroken years after its founding in 1929, wrapping itself in revolutionary rhetoric while operating a sophisticated system of co-optation, corruption, and controlled dissent. It was, critics argued, the revolution institutionalised and embalmed. The PRI finally lost the presidency in 2000, but debates about whether the revolution’s promises of land, justice, and dignity have ever been truly fulfilled continue to animate Mexican politics, from the Zapatista uprising in Chiapas in 1994 (which chose 1 January, the day NAFTA took effect, as its moment of symbolic protest) to the present day.

Zapata’s face appears on murals in villages across Latin America. Villa’s name adorns stadiums and boulevards. The revolution lives not merely as history but as argument: about what Mexico owes its poor, its indigenous peoples, its workers — and what it still has not delivered.

Ten years of fire remade a nation. One hundred and fifteen years later, Mexicans are still deciding what that nation should be.

Leave a Reply