The First Anglo-Afghan War stands as one of the most catastrophic military ventures in British imperial history. What began as a confident assertion of power in Central Asia ended in one of the most complete defeats ever suffered by the British Empire, leaving an entire army destroyed and providing enduring lessons about the perils of foreign intervention in Afghanistan.

The Great Game and growing tensions

The conflict emerged from the broader context of the “Great Game“, the strategic rivalry between the British and Russian empires for influence in Central Asia. As Britain consolidated its control over India through the East India Company, officials in London and Calcutta became increasingly paranoid about Russian expansion southward toward the subcontinent.

Afghanistan occupied a crucial position in this geopolitical chess match.

The mountainous kingdom served as a natural buffer between Russian-influenced Persia and British India, making its allegiance a matter of imperial security. The British feared that Russian agents were working to bring Afghanistan into their sphere of influence, potentially opening a route for invasion of India.

The immediate catalyst came from the complex succession politics within Afghanistan itself. Dost Mohammad Khan, the Emir of Afghanistan, had approached the British for support in his territorial disputes with the Sikh Empire. When British officials, led by Governor-General Lord Auckland, proved unresponsive to his overtures, Dost Mohammad began entertaining Russian diplomatic advances.

The decision to go to war

Lord Auckland, influenced by his advisors, William Macnaghten and Alexander Burnes, became convinced that Afghanistan, under Dost Mohammad, posed an existential threat to British India. In a fateful decision, the British chose to pursue regime change, planning to depose Dost Mohammad and install Shah Shuja, a former ruler who had been living in exile under British protection.

The Tripartite Treaty of 1838, signed between Britain, the Sikh Empire, and Shah Shuja, provided the legal framework for intervention. The British promised to restore Shah Shuja to the throne and maintain him there, while he agreed to conduct his foreign policy in accordance with British interests.

The invasion and initial success

In December 1838, the Army of the Indus began its march toward Afghanistan. This massive force consisted of approximately 21,000 troops, including British regulars, East India Company sepoys, and Shah Shuja’s contingent, accompanied by an enormous baggage train of 38,000 camp followers and 30,000 camels.

The invasion initially proceeded with surprising ease. The British forces advanced through the Bolan Pass and captured the fortress city of Ghazni in July 1839 through a daring night assault. Dost Mohammad, realising the hopelessness of resistance, fled to the northern regions of his kingdom, and by August 1839, Shah Shuja was ceremonially installed on the throne in Kabul.

For nearly two years, the British occupation appeared successful. Shah Shuja ruled from the Bala Hissar fortress, protected by British bayonets, while British officials administered the country’s affairs. William Macnaghten served as envoy and minister, effectively governing Afghanistan from behind the scenes.

The seeds of rebellion

However, the apparent stability masked growing resentment among the Afghan population. Shah Shuja was widely viewed as a British puppet, lacking legitimacy among his own people. The heavy-handed British administration, cultural insensitivity, and the visible foreign occupation increasingly alienated Afghan tribes and religious leaders.

Economic factors further fueled discontent. The British had reduced subsidies to tribal chiefs who had previously been bought off by Dost Mohammad, creating powerful enemies. Meanwhile, the cost of maintaining the occupation was proving astronomical, leading to penny-pinching measures that further antagonised local populations.

Religious sentiment also played a crucial role. Many Afghans viewed the British presence as an affront to Islam, and influential religious leaders began preaching jihad against the foreign invaders. The situation was particularly volatile in the countryside, where traditional tribal structures chafed under British attempts at centralised control.

The explosion of 1841

The fragile peace was shattered in November 1841 when Afghan rebels assassinated Alexander Burnes, the British resident in Kabul, along with his staff. This murder sparked a general uprising throughout the country. Within days, the British cantonment in Kabul was under siege, cut off from supplies and reinforcements.

The British military response proved disastrously inadequate. The cantonment’s defences were poorly designed, situated on low ground that was overlooked by hills, which rebels quickly occupied. General William Elphinstone, the elderly and indecisive British commander, seemed paralysed by the crisis, unable to mount effective military operations or negotiate a meaningful settlement.

William Macnaghten, still believing he could manage the situation through diplomacy and bribery, entered into negotiations with the rebel leaders. His efforts culminated in a treacherous meeting on 23 December 1841, where he was murdered by Akbar Khan, Dost Mohammad’s son, who had emerged as a key leader of the resistance.

The retreat from Kabul

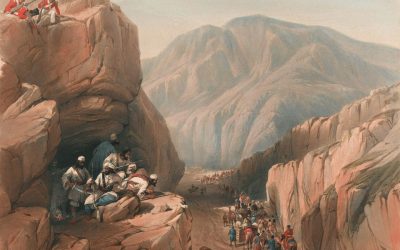

With Macnaghten dead and the military situation hopeless, the British agreed to a treaty that promised safe passage for their forces to Jalalabad in exchange for evacuating Afghanistan and returning Dost Mohammad to power. On 6 January 1842, the retreat began. It was one of the most disastrous military withdrawals in history.

The retreating column consisted of approximately 4,500 British and Indian troops plus 12,000 camp followers, including women and children. Almost immediately, the Afghans began attacking the column despite the supposed guarantee of safe passage. The British forces, strung out over miles of difficult terrain, proved vulnerable to constant harassment by Afghan fighters who knew the country intimately.

The retreat quickly became a nightmare of cold, hunger, and relentless attacks. The January weather in the Hindu Kush was brutal, with temperatures far below freezing. Many soldiers, inadequately clothed for the conditions, simply froze to death. Others fell to Afghan knives and jezails (long-barreled muskets) in countless skirmishes along the route.

The massacre at Gandamak

The final catastrophe occurred at the village of Gandamak on 13 January 1842. The remnants of the British force, around 65 officers and men of the 44th Regiment of Foot, along with a few hundred sepoys, made their last stand on a hilltop. Surrounded and overwhelmed, they fought to the death with bayonets and empty muskets used as clubs.

William Barnes Wollen, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Of the entire retreating force, only one man, Dr William Brydon, reached the British garrison at Jalalabad alive. His arrival, wounded and alone, brought the first news of the disaster to the outside world. The image of Brydon’s solitary figure approaching the walls of Jalalabad became an iconic representation of the catastrophe.

British response and the “Army of Retribution”

The destruction of the Kabul garrison sent shockwaves throughout British India and reached London with devastating impact. The prestige of British arms, carefully cultivated over decades of imperial expansion, suffered a tremendous blow. Public opinion demanded vengeance and the rescue of prisoners still held in Afghan hands.

General George Pollock was dispatched with the “Army of Retribution” to restore British honour. In September 1842, British forces reoccupied Kabul, destroyed the great bazaar in revenge for the massacre, and rescued the remaining prisoners. However, the British had learned their lesson about the impossibility of governing Afghanistan and withdrew completely by the end of 1842.

Dost Mohammad was restored to his throne, exactly where the British had found him four years earlier. The entire costly enterprise had achieved nothing except to demonstrate the limits of British power and the fierce independence of the Afghan people.

Consequences and historical significance

The First Anglo-Afghan War had profound consequences for British imperial policy and strategic thinking. The financial cost was enormous, estimated at over £15 million—a vast sum for the time. More importantly, the human cost was staggering, with thousands of British and Indian soldiers dead and an entire army effectively annihilated.

The disaster forced a fundamental reassessment of British strategy on the Northwest Frontier. Future policy would rely more on diplomatic agreements with buffer states rather than direct occupation. The British learned to work with existing rulers rather than attempting to impose their own candidates.

The war also established Afghanistan’s reputation as the “graveyard of empires,” a characterisation that would prove prophetic for future foreign interventions. The fierce resistance encountered by British forces demonstrated the difficulty of conquering and holding Afghanistan, lessons that would be forgotten and relearned by subsequent powers.

For Afghanistan itself, the war reinforced the country’s independence and strengthened resistance to foreign domination. The successful expulsion of British forces became part of Afghan national mythology, inspiring future resistance movements against foreign invaders.

Enduring lessons

The First Anglo-Afghan War offers timeless lessons about the limits of military power and the dangers of imperial overreach. The British failure stemmed from fundamental misunderstandings about Afghan society, the legitimacy of imposed governments, and the sustainability of foreign occupation.

The conflict demonstrated that military superiority alone cannot guarantee political success, especially when occupying forces lack popular legitimacy. The British could win battles and capture cities, but they could not win the loyalty of the Afghan people or establish a stable government that could survive without foreign support.

The war also underscored the importance of understanding local culture and politics prior to intervention. British officials consistently misread Afghan society, underestimating the strength of tribal traditions and religious sentiment while overestimating their ability to reshape the country according to their preferences.

Perhaps most significantly, the First Anglo-Afghan War illustrated the unforgiving nature of Afghan geography and climate, factors that have challenged every foreign army that has attempted to control the country. The mountains that make Afghanistan a natural fortress also make it a trap for occupying forces, as the British learned at a terrible cost.

The echoes of this 19th-century disaster would resonate through subsequent conflicts in Afghanistan, serving as a sobering reminder that military might alone cannot overcome determined resistance on difficult terrain. The First Anglo-Afghan War stands as a cautionary tale about the perils of imperial ambition and the enduring strength of people fighting for their independence on their own soil.

Leave a Reply