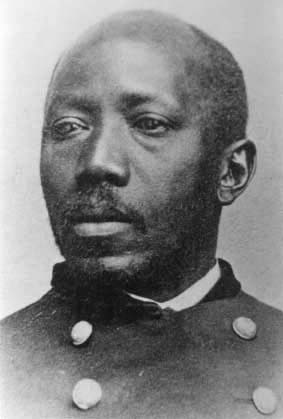

Martin Robison Delany was many things in one lifetime — abolitionist, doctor, newspaper editor, explorer, political theorist, soldier, and arguably the first major Black nationalist thinker in American history. Born free in 1812 in what was then Virginia slave country, Delany grew up with the constant awareness that freedom on paper did not mean safety in practice. By the time he died in 1885, he had helped shape nearly every major Black political debate of the nineteenth century: integration or separation, protest or self-defence, America or emigration.

If Frederick Douglass was the era’s great persuader, Delany was its uncompromising realist.

He did not simply ask America to live up to its ideals. He doubted it ever would.

Early life: Freedom under threat

Delany was born in Charles Town, Virginia, to a free mother and an enslaved father. Under Virginia law, a child inherited their mother’s status, which made them legally free. But legal freedom did little to protect Black families. Teaching enslaved or free Black children to read was illegal, and Delany’s mother risked arrest by secretly educating her children. When local whites discovered this, she fled with the family to Pennsylvania, a quiet act of resistance that shaped Delany’s lifelong belief that Black survival required bold, practical action, not patience.

In Pennsylvania, he apprenticed as a barber, then educated himself through reading and eventually medical study. Like many Black intellectuals of the time, he built his career through self-teaching and community networks rather than formal institutions that largely excluded him.

From the beginning, Delany believed knowledge was a weapon.

The abolitionist journalist

In the 1840s, Delany entered politics through print. He began writing against slavery and racial injustice, quickly gaining a reputation for sharp, unsentimental analysis. His big break came when he joined Frederick Douglass as co-editor of The North Star, one of the most important abolitionist newspapers in the United States.

The partnership was powerful but tense.

Douglass argued that Black Americans should claim their rights within the United States. Delany increasingly believed the country was structurally hostile to Black freedom. While Douglass spoke the language of moral appeal, Delany spoke the language of self-determination and power.

Their disagreement foreshadowed a debate that still echoes today: reform the system, or build something separate from it?

Delany leaned toward separation.

Physician, intellectual, and “Father of Black Nationalism”

Delany studied medicine at Harvard Medical School in the early 1850s, becoming one of the first three Black students admitted. White students protested his presence so aggressively that the school expelled him along with the other black students, Daniel Laing, Jr. and Isaac H. Snowden. The message was clear: even talent and education would not guarantee acceptance.

This moment hardened his thinking.

In 1852, he published The Condition, Elevation, Emigration, and Destiny of the Colored People of the United States, one of the most important Black political texts of the century. In it, Delany argued bluntly:

America would never willingly grant Black people equality.

Therefore, Black people must build independent power, economically, politically, and geographically.

He advocated Black-controlled businesses, land ownership, and even the possibility of founding settlements abroad. Decades before Marcus Garvey or Pan-Africanism, Delany was already sketching the intellectual framework.

That’s why historians often call him the “father of Black nationalism.”

The African expedition

Unlike many armchair theorists, Delany tested his ideas in the real world. In 1859–60, he travelled to West Africa, negotiating with leaders in what is now Nigeria to establish a potential settlement for Black Americans seeking autonomy.

His goal wasn’t simply escape. It was sovereignty.

He imagined skilled Black Americans helping build modern, independent African societies while freeing themselves from American racism. The American Civil War interrupted the project, but the expedition marked one of the earliest serious attempts at transatlantic Black political collaboration.

Long before “Back to Africa” movements became widely known, Delany had already walked the coastlines himself.

Civil War Officer

When the Civil War began, Delany’s focus shifted again. Emigration could wait. Slavery had to die first.

He helped recruit Black soldiers for the Union Army and became the first Black man to receive a field officer’s commission in the US Army, earning the rank of Major. That alone was groundbreaking.

In uniform, he embodied a radical image for the era: a Black man not begging for freedom, but fighting for it as an officer commanding troops.

His service wasn’t symbolic. It was proof that Black citizenship could be asserted through action and sacrifice.

Reconstruction and later years

After the war, Delany briefly worked with the Freedmen’s Bureau and entered politics during Reconstruction. But like many Black leaders, he became disillusioned as white backlash dismantled progress. He even made controversial tactical compromises later in life, supporting conservative Democrats in South Carolina at one point, a move that damaged his reputation among some former allies.

Yet even this reflected his pragmatic streak.

Delany was never driven solely by ideology. He was driven by survival and leverage. He backed whichever strategy he believed might preserve Black autonomy in a rapidly closing political window.

It didn’t always make him popular, but it made him honest.

Legacy

Delany doesn’t fit neatly into heroic narratives. He could be stubborn, severe, even divisive. But he was also ahead of his time.

Many ideas later associated with twentieth-century movements — Black economic independence, self-defence, Pan-African connections, scepticism toward white liberal promises — first appear in Delany’s writing.

He anticipated:

- Marcus Garvey’s Black nationalism

- Malcolm X’s self-determination philosophy

- Pan-African solidarity movements

- debates about integration vs. autonomy that still shape politics today

Where Douglass asked America to change, Delany prepared for the possibility that it wouldn’t.

That tension, hope versus realism, defined Black political thought for generations.

Final assessment

Martin Robison Delany forces us to confront an uncomfortable truth: sometimes the most visionary thinkers are not the most celebrated. He lacked Douglass’s rhetorical polish or Lincoln’s mythic status, but he possessed something just as powerful: strategic clarity.

He looked at the United States in the 1800s and concluded:

We cannot rely on goodwill. We must build our own power.

It was a hard message. It still is.

But history keeps proving he wasn’t wrong.

Leave a Reply