For nearly half a century, one man’s shadow stretched across the Caribbean, defying the world’s most powerful nation just ninety miles from its shores. Fidel Castro, the bearded revolutionary in olive fatigues, transformed Cuba from an American client state into a socialist beacon that inspired liberation movements worldwide while simultaneously serving as a symbol of authoritarian rule and economic stagnation. His death in 2016 closed a chapter on one of the twentieth century’s most polarising figures—a leader venerated by supporters as an anti-imperialist champion and condemned by critics as a dictator who crushed dissent and impoverished his people.

From privilege to revolution

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz was born on 13 August 1926, in Birán, a small town in eastern Cuba. Contrary to the romantic peasant origins often attributed to revolutionaries, Castro came from relative privilege. His father, Ángel Castro, was a wealthy Spanish immigrant who owned a successful sugarcane plantation. This comfortable upbringing afforded young Fidel an elite Jesuit education in Havana, where he proved himself an exceptional student and athlete, particularly in basketball and baseball.

At the University of Havana, Castro studied law but found himself increasingly drawn to politics during a tumultuous period in Cuban history. The university was a hotbed of political activism, and Castro became involved in student protests and the broader anti-government movement. It was here that his political consciousness crystallised around ideas of Cuban nationalism, anti-imperialism, and social justice. He witnessed firsthand the corruption of Cuban politics, the vast inequality between rich and poor, and the overwhelming American economic and political influence over the island.

After graduating in 1950, Castro practised law briefly, often representing poor clients who could not afford legal services. But his attention remained fixed on politics. When Fulgencio Batista seized power in a 1952 coup, cancelling elections that Castro had hoped to contest, the young lawyer concluded that legal paths to change were closed. Cuba needed revolution.

The path to power

On 26 July 1953, Castro led approximately 160 poorly armed rebels in an audacious attack on the Moncada Barracks in Santiago de Cuba. The assault was a military disaster. More than sixty rebels were killed, and Castro was captured. Yet the failed attack became a propaganda victory. At his trial, Castro delivered his famous “History Will Absolve Me” speech, a powerful indictment of the Batista regime that outlined his vision for Cuba’s future. Sentenced to fifteen years in prison, he served less than two before being released in a general amnesty.

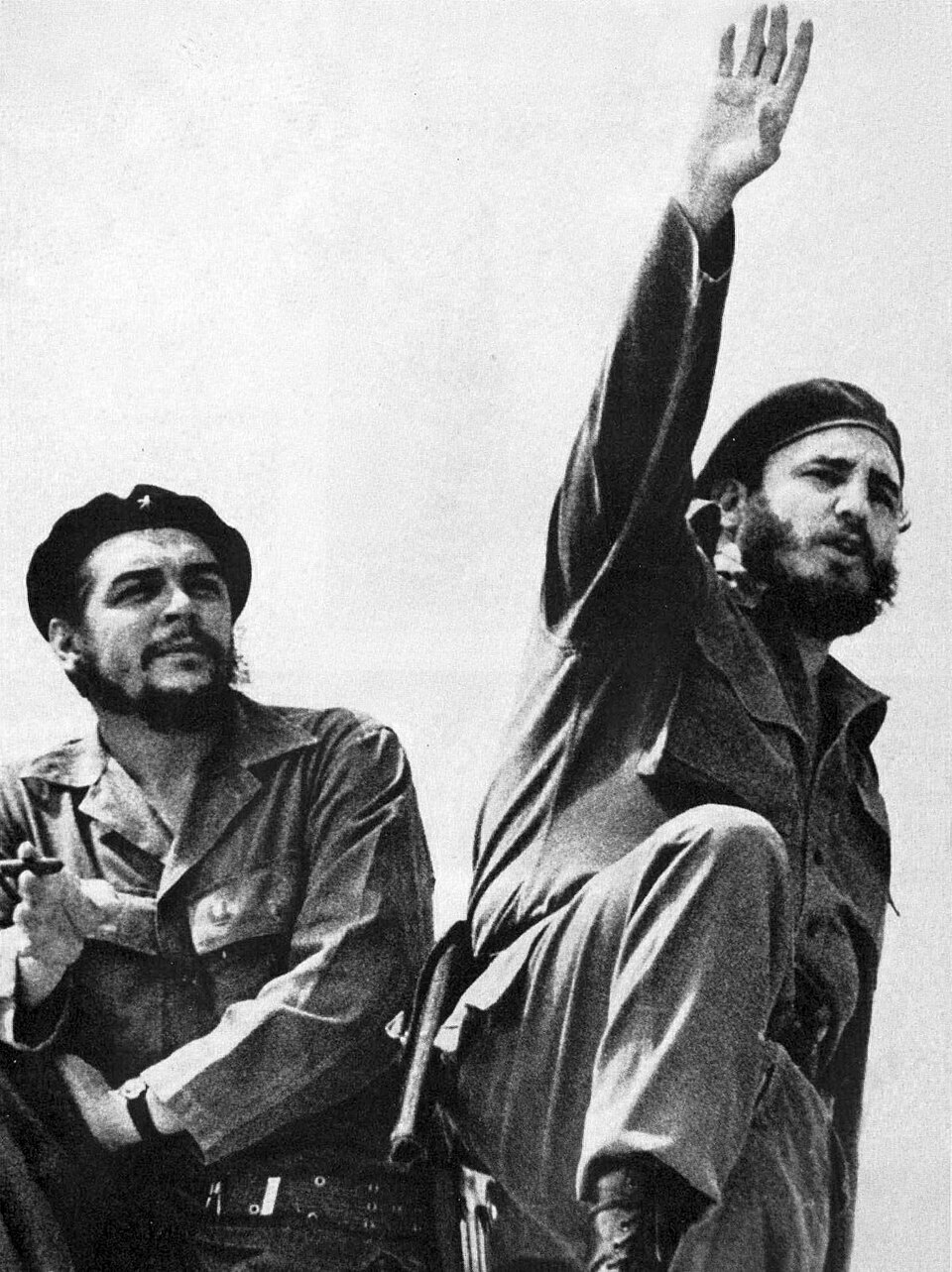

Alberto Korda, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Castro went into exile in Mexico, where he met Ernesto “Che” Guevara, the Argentine doctor who would become his closest revolutionary comrade. Together, they organised a new uprising. In December 1956, Castro, Guevara, and eighty others sailed from Mexico aboard the yacht Granma, landing in Cuba to begin a guerrilla war. The landing was nearly catastrophic. Ambushed by Batista’s forces, only about twenty rebels survived the initial encounter and escaped into the Sierra Maestra mountains.

From these mountains, Castro built a formidable guerrilla movement. He proved himself a master of both military tactics and propaganda, granting interviews to foreign journalists and broadcasting radio messages that spread his message across Cuba. His forces gained strength not just through military victories but by winning popular support, implementing literacy programs and basic healthcare in areas they controlled, and presenting themselves as the antidote to Batista’s corruption and brutality.

By late 1958, Batista’s regime was collapsing. Multiple guerrilla fronts had opened, the urban underground movement was growing, and the dictator had lost American support. On 1 January 1959, Batista fled Cuba, and Castro’s forces marched triumphantly into Havana. At age thirty-two, Fidel Castro had achieved what seemed impossible just two years earlier.

Building a socialist state

Initially, Castro’s revolution was not explicitly communist. The early government included moderate figures, and Castro spoke of restoring democracy and the 1940 constitution. However, the revolution quickly radicalised. Castro implemented sweeping land reforms, nationalising large estates and foreign-owned properties. When American companies protested, relations with the United States deteriorated rapidly.

The question of whether Castro was always a communist or became one out of strategic necessity remains debated by historians. What is clear is that by 1961, as tensions with the United States escalated, culminating in the Bay of Pigs invasion by CIA-backed Cuban exiles, Castro formally declared Cuba a socialist state and allied the island with the Soviet Union. This alliance would define Cuba for the next three decades, providing economic lifelines and military protection while also constraining Castro’s independence.

Castro’s domestic policies profoundly transformed Cuban society. His government implemented universal healthcare and education systems that became sources of genuine pride. Cuba achieved literacy rates and health outcomes that rivaled developed nations, accomplishments impressive for a small, poor Caribbean island facing an American economic embargo. Doctors and teachers were sent to serve in rural areas, and university education became free. These achievements in human development became central to Castro’s legacy among supporters.

However, these gains came at an enormous cost. Castro established a one-party state that tolerated no opposition. Independent media was eliminated, political dissidents were imprisoned, and thousands of Cubans faced persecution for their beliefs or sexual orientation. The regime created an extensive security apparatus to monitor citizens and suppress dissent. Hundreds of thousands of Cubans chose exile, creating vibrant diaspora communities, particularly in Miami, that became centres of anti-Castro activism.

Economically, Castro’s centrally planned economy struggled. After initial improvements, productivity stagnated. The regime’s inefficiencies, compounded by the American embargo and dependence on Soviet subsidies, created chronic shortages of basic goods. While healthcare and education flourished, consumer goods remained scarce, housing deteriorated, and the economy failed to develop beyond sugar and tourism.

The international revolutionary

Castro’s influence extended far beyond Cuba’s shores. He saw himself as part of a global revolutionary movement and committed Cuban resources to supporting liberation struggles worldwide. Cuban troops fought in Angola against South African-backed forces, helping to secure that country’s independence and dealing apartheid South Africa a significant military defeat. Cuban soldiers and advisors served in Ethiopia, Syria, Nicaragua, and numerous other countries. These interventions made Cuba a major player in Cold War geopolitics despite its small size.

Castro became an icon for anti-imperialist movements globally, particularly in Latin America, Africa, and the developing world. His willingness to defy the United States resonated with those who saw American power as the primary obstacle to their own liberation. Leaders from Nelson Mandela to Hugo Chávez acknowledged Castro’s influence and support.

The 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis represented Castro’s most dangerous moment on the world stage. When the Soviet Union placed nuclear missiles in Cuba, the world came to the brink of nuclear war. Castro reportedly advocated for using the weapons if the United States invaded, a position that alarmed even his Soviet allies. The crisis ended with the Soviets removing the missiles in exchange for American promises not to invade Cuba and to remove missiles from Turkey, but Castro felt betrayed by the settlement made without his consultation.

Surviving against the odds

Perhaps Castro’s most remarkable achievement was simply surviving. The CIA attempted to assassinate him hundreds of times through increasingly bizarre schemes. The United States maintained a comprehensive economic embargo for over fifty years, attempting to economically strangle the regime. Ten American presidents, from Eisenhower to Obama, tried various strategies to remove or undermine him. Castro outlasted them all.

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 seemed likely to finally doom Castro’s regime. Cuba lost its primary benefactor almost overnight, with Soviet subsidies that had propped up the economy suddenly disappearing. The 1990s “Special Period” brought severe hardship, with food rationing, blackouts, and economic contraction. Yet somehow, Castro’s government survived this crisis too, eventually finding new economic models, including tourism and, later, Venezuelan oil subsidies.

Castro officially stepped down from power in 2006 due to illness, transferring authority to his brother Raúl. Even in semi-retirement, he remained an influential voice, writing regular opinion columns and occasionally appearing in public. His death on 25 November 2016, at age ninety, marked the end of an era.

A contested legacy

Assessing Castro’s legacy requires grappling with profound contradictions. He championed the poor and marginalised, yet presided over a system that imprisoned dissidents and denied basic freedoms. He built a society with impressive health and education outcomes, yet one where citizens couldn’t freely speak, travel, or choose their government. He stood up to superpower bullying, yet allied with another superpower and imposed his will on smaller nations.

For supporters, Castro represented resistance to imperialism and the possibility of an alternative to American-dominated capitalism. They point to Cuba’s healthcare system, its medical internationalism, its survival against overwhelming odds, and its refusal to bow to American pressure. They note that many of Cuba’s economic problems stemmed from the embargo and external pressure rather than purely internal failures.

For critics, Castro was a tyrant who hijacked a legitimate revolution and imposed decades of authoritarian rule. They emphasise the political prisoners, the Cubans who risked death fleeing on rafts, the gay Cubans sent to labour camps, the writers and artists censored or exiled, and the economic stagnation that left Cuba frozen in time. They argue that Cuba’s achievements could have been realised without dictatorship and that Castro’s anti-imperialism was selective, given his alliance with the Soviets.

The truth encompasses both perspectives. Castro was undeniably charismatic, intelligent, and politically skilled. He was also authoritarian, intolerant of dissent, and willing to sacrifice individual freedom for his vision of collective good. He genuinely believed in his revolutionary project and lived relatively modestly compared to many dictators, yet he also enjoyed the prerogatives of absolute power for half a century.

Enduring impact

Castro’s historical significance is undeniable. He demonstrated that small nations could maintain independence from superpowers, providing a model that inspired other leaders. He showed that revolutionary movements could succeed against seemingly impossible odds. He helped accelerate decolonisation in Africa and supported anti-apartheid struggles. His Cuba trained thousands of doctors who served throughout the developing world.

Yet he also demonstrated the limitations and costs of revolutionary socialism, the dangers of concentrated power, and how idealism can curdle into authoritarianism. Post-Castro Cuba under Raúl Castro and then Miguel Díaz-Canel has slowly implemented market reforms while maintaining political control, suggesting that some evolution of the system Fidel built was necessary.

For the United States, Castro represented a foreign policy failure and a source of frustration that lasted generations. The inability to dislodge him just ninety miles from Florida became a symbol of American limits. The embargo that was meant to hasten his fall instead provided him with a convenient excuse for economic failures while allowing him to cast himself as David against Goliath.

Fidel Castro’s Cuba was an anachronism, a Cold War relic that survived into the twenty-first century. His revolution began with promises of freedom and democracy but delivered neither, even as it achieved real gains in health and education. He was simultaneously a champion of the oppressed and an oppressor, an anti-imperialist who imposed his will on others, a visionary leader and a rigid ideologue.

History’s ultimate judgment on Fidel Castro will likely remain divided, reflecting the deep polarisation his life and revolution generated. What cannot be disputed is his immense impact on the twentieth century, his role in shaping Latin American politics, and his demonstration that willpower, tactical skill, and historical timing can allow even small nations to punch far above their weight on the world stage. Whether that punch landed for good or ill depends largely on where one stands, a fitting ambiguity for a figure who thrived on confrontation and contradiction throughout his remarkable, tumultuous life.

Leave a Reply