Few figures in twentieth-century history have inspired as much devotion and provoked as much controversy as Ernesto “Che” Guevara, the Argentine-born revolutionary whose life and death transformed him into an enduring global icon.

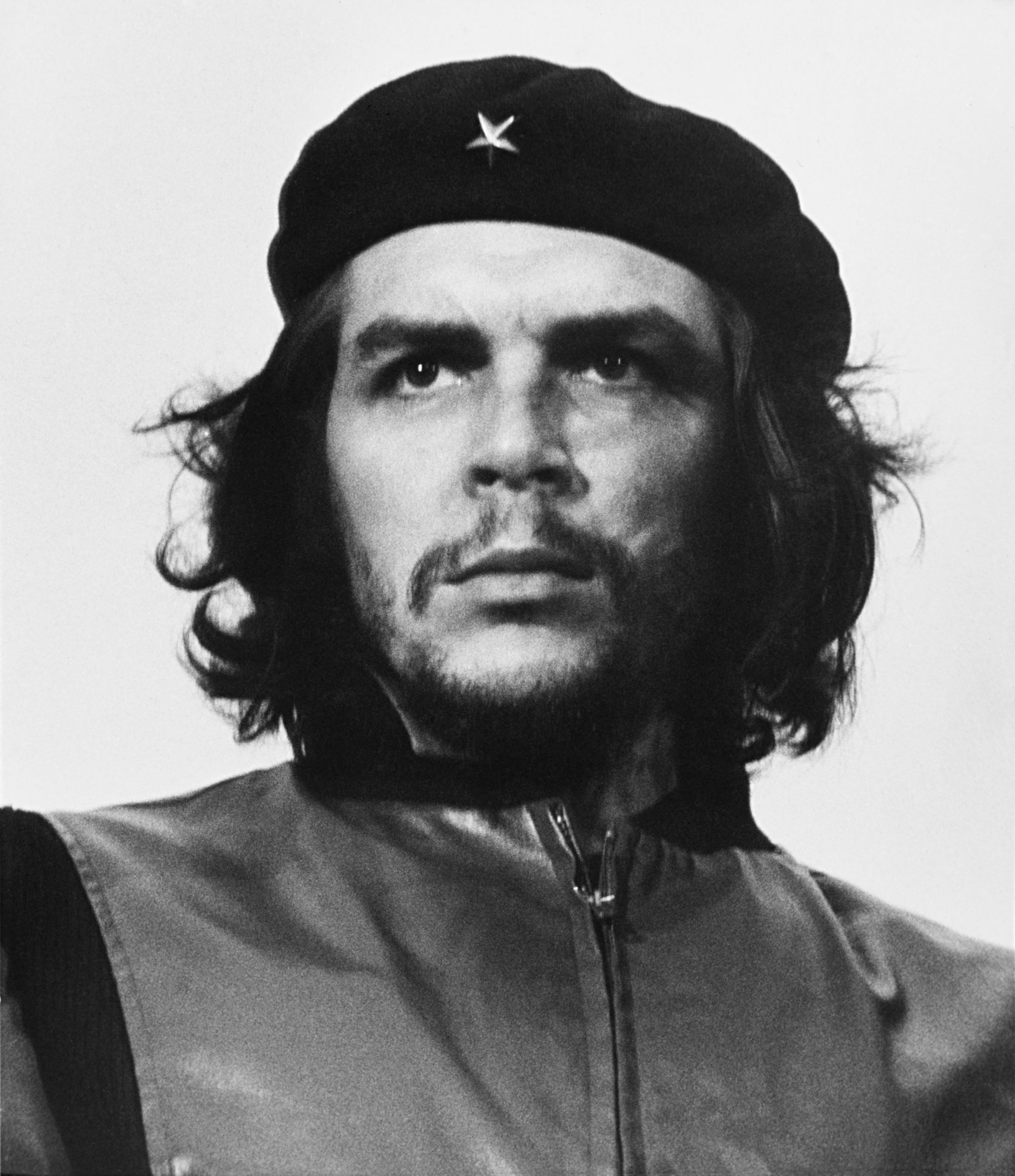

The face is instantly recognisable: dark beret, penetrating gaze, wind-tousled hair. Alberto Korda’s 1960 photograph “Guerrillero Heroico” has become one of the most reproduced images in history, adorning everything from t-shirts to protest banners to gallery walls. Yet the man behind the iconography remains a figure of intense controversy and contradiction. He is simultaneously celebrated as a selfless revolutionary hero and condemned as a ruthless ideologue responsible for numerous executions. Ernesto “Che” Guevara’s life and legacy continue to provoke passionate debate more than half a century after his death.

The making of a revolutionary

Ernesto Guevara de la Serna was born on 14 June 1928, in Rosario, Argentina, into a middle-class family of Irish and Spanish descent. His childhood was marked by severe asthma, a condition that would plague him throughout his life but seemed only to strengthen his determination. His mother, Celia de la Serna, was a woman of progressive views who introduced young Ernesto to leftist literature and political discussion. His father, Ernesto Guevara Lynch, was an engineer and entrepreneur whose business ventures met with mixed success.

The young Guevara was a voracious reader, devouring works by Pablo Neruda, John Keats, Robert Frost, and Karl Marx. He excelled at chess and developed a passion for rugby, refusing to let his asthma prevent him from participating in physical activities. This early defiance of his physical limitations would become characteristic of his approach to life’s obstacles.

In 1948, Guevara enrolled at the University of Buenos Aires to study medicine, apparently motivated by a desire to understand his own condition and help others suffering from similar afflictions. But it was during his medical studies that the trajectory of his life would fundamentally shift. In 1952, he embarked on a motorcycle journey across South America with his friend Alberto Granado, a trip later immortalised in his posthumously published travel diary and the 2004 film “The Motorcycle Diaries.” (Read for free).

This journey proved transformative. Travelling through Chile, Peru, Colombia, and Venezuela, Guevara witnessed firsthand the grinding poverty, social inequality, and exploitation that characterised much of Latin America. He worked briefly at a leper colony in Peru, where he observed the dignity of the afflicted and the inadequacy of medical solutions to problems rooted in social injustice. He saw American-owned mines extracting wealth while local populations lived in destitution. He encountered indigenous communities marginalised by descendants of European colonisers. These experiences radicalised the young medical student, convincing him that Latin America’s problems were systemic and required revolutionary rather than reformist solutions.

The Cuban Revolution

After completing his medical degree in 1953, Guevara travelled through Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, and El Salvador. In Guatemala, he witnessed the CIA-backed coup that overthrew the democratically elected government of Jacobo Árbenz, an experience that deepened his anti-American sentiment and convinced him that meaningful change would have to be defended by armed force.

It was in Mexico City in 1955 that Guevara met Fidel Castro and his brother Raúl. Castro was planning an expedition to Cuba to overthrow the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista. Guevara, now going by the nickname “Che”—a common Argentine expression roughly equivalent to “hey” or “buddy”—joined the revolutionary movement as its doctor. When Castro expressed doubts about bringing an Argentine into a Cuban revolution, Guevara reportedly declared his commitment to revolution wherever it was needed.

On 2 December 1956, eighty-two revolutionaries, including Che, departed Mexico aboard the yacht Granma, bound for Cuba. The landing was nearly disastrous; they arrived late and at the wrong location, and were quickly engaged by Batista’s forces. Only about twenty men survived the initial encounter and escaped into the Sierra Maestra mountains.

Public domain

What followed was a two-year guerrilla campaign that would make Guevara’s reputation as a military tactician and ruthless commander. Despite his lack of formal military training, Che proved to be a natural guerrilla fighter and leader. He was known for his discipline, his willingness to share the hardships of his men, and his severe punishment of desertion or betrayal. He established schools and clinics in areas under rebel control, applying his medical knowledge even as he led combat operations.

Guevara commanded the decisive Battle of Santa Clara in December 1958, where his forces derailed an armoured train carrying government troops and weapons—a spectacular victory that effectively sealed Batista’s fate. On1 January 1959, Batista fled Cuba, and the revolutionaries took power. Che Guevara had transformed from an asthmatic Argentine doctor into one of the most famous guerrilla commanders in the world.

Revolutionary government

In the new Cuban government, whilst Fidel Castro ruled as Prime Minister, Guevara assumed several key positions. He served as president of the National Bank of Cuba (allegedly signing the new currency with his nickname “Che”) and later as Minister of Industries. His economic policies were controversial and often unsuccessful. A romantic revolutionary more comfortable in the mountains than in bureaucratic offices, Guevara’s economic initiatives were guided more by ideological purity than pragmatic considerations.

He championed rapid industrialisation and agricultural collectivisation, often with disappointing results. His management of sugar production, Cuba’s primary export, was marked by ambitious targets that frequently went unmet. He advocated for “moral incentives” over material ones, believing that revolutionary consciousness, rather than wages or bonuses, should motivate workers, a theory that proved difficult to implement in practice.

However, Guevara’s role in the early revolutionary tribunals would become one of the most controversial aspects of his legacy. As commander of La Cabaña fortress prison, he oversaw the trials and executions of hundreds of individuals accused of war crimes under the Batista regime. Estimates of those executed vary widely, from several hundred to over a thousand. Guevara made no apologies for these actions, viewing them as necessary revolutionary justice. His writings and speeches from this period reveal a man convinced that violence in the service of revolution was not only justified but necessary.

The internationalist

Guevara never saw revolution as limited to Cuba. He believed in internationalism and in exporting revolution to other parts of Latin America, Africa, and Asia. In 1964, he addressed the United Nations General Assembly, delivering a scathing critique of imperialism and defending revolutionary movements worldwide. His speech, while ideologically rigid, showcased his evolution into a global revolutionary figure.

In 1965, Guevara renounced his Cuban citizenship and ministerial positions and disappeared from public view. In a farewell letter to Fidel Castro, he wrote of his intention to fight imperialism wherever he could. He first travelled to the Congo, where he spent several months supporting Laurent-Désiré Kabila’s rebellion against the government. The mission was a failure, hampered by internal conflicts, lack of popular support, and Guevara’s inability to adapt his Cuban guerrilla model to African conditions.

Undeterred, Guevara next set his sights on Bolivia. He believed the country’s strategic position and poor, indigenous population made it ripe for revolution. In November 1966, he arrived in Bolivia with a small group of Cuban and Bolivian fighters to establish a guerrilla foco—a revolutionary focal point that would inspire a broader uprising.

The Bolivian campaign proved disastrous. Guevara failed to gain support from the local peasantry, who were suspicious of foreign fighters and had recently received land under government reforms. The Bolivian Communist Party refused to support the effort. Bolivian special forces, trained by the CIA, tracked his movements. Suffering from asthma attacks, operating in unfamiliar terrain, and increasingly isolated, Guevara’s force dwindled through desertion, capture, and death.

Death and mythmaking

On 8 October 1967, Bolivian forces captured Guevara in the mountains near La Higuera. The following day, acting on orders from the Bolivian government and with CIA approval, a Bolivian sergeant executed the wounded revolutionary. Guevara was thirty-nine years old.

The circumstances of his death, captured, wounded, and executed rather than killed in combat, immediately began his transformation into a martyr. Photographs of his corpse, laid out in a laundry room with his eyes open, evoked comparisons to images of Christ. His body was secretly buried in an unmarked grave (later discovered and returned to Cuba in 1997, where it now rests in a mausoleum in Santa Clara).

The contested legacy

Che Guevara’s legacy is perhaps more debated than that of any other twentieth-century revolutionary. To supporters, he represents the possibility of principled resistance to oppression, a man who sacrificed personal comfort and ultimately his life for his beliefs. They point to his genuine commitment to the poor, his willingness to live according to his principles, and his opposition to imperialism and exploitation. In much of Latin America and the developing world, his image symbolises resistance to injustice.

To critics, Guevara was a totalitarian ideologue whose romantic vision of revolution led to economic failure and human suffering. They emphasise the executions he ordered, his intolerance of dissent, his failed economic policies in Cuba, and his willingness to risk nuclear war during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Conservative critics, particularly in the United States and among Cuban exiles, view him as a murderer and a fanatic whose mythology obscures his brutal reality.

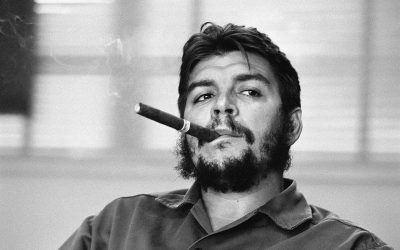

The transformation of Che’s image into a commercial commodity represents one of the great ironies of modern capitalism. The face that represented revolutionary anti-capitalism now sells merchandise for multinational corporations. This commercialisation has been criticised by those who knew him and by scholars as a trivialisation of his ideas and a testament to capitalism’s ability to absorb and neutralise even its most strident critics.

The complex revolutionary

The truth about Che Guevara resists simple categorisation. He was undoubtedly brave, principled, and willing to sacrifice comfort and ultimately life itself for his beliefs. His writings reveal a man of genuine intellectual curiosity and literary talent. His medical training and work with lepers showed a capacity for compassion. He lived modestly, refusing special privileges, and seemed genuinely committed to egalitarian ideals.

Yet he was also dogmatic, intolerant of dissent, and willing to employ extreme violence in pursuit of his goals. His economic theories proved largely unworkable. His guerrilla model, while successful in Cuba’s unique circumstances, failed elsewhere. His commitment to armed revolution resulted in deaths not only of his enemies but of many who followed him.

Conclusion

More than fifty years after his death, Ernesto “Che” Guevara remains a powerful and contested symbol. For some, he embodies selfless dedication to social justice and the possibility of meaningful change through revolutionary action. For others, he represents the dangers of ideological rigidity and the human cost of revolutionary violence.

Perhaps what makes Guevara’s legacy so enduring is precisely this complexity. He cannot be easily dismissed or wholly embraced. His life raises fundamental questions about the relationship between means and ends, the possibility of revolutionary change, the role of violence in social transformation, and the price of unwavering commitment to an ideal.

In an era of widespread cynicism about politics and activism, Guevara’s willingness to risk everything for his beliefs continues to resonate, even among those who reject his methods or ideology. Yet his failures and excesses serve as cautionary tales about the dangers of revolutionary romanticism and ideological certainty.

The face on the t-shirt conceals a complicated human being, neither the secular saint of revolutionary mythology nor the demonic totalitarian of his harshest critics, but something more ambiguous and ultimately more interesting. Understanding Che Guevara requires looking beyond the iconic image to examine both his genuine commitments and his serious flaws, to acknowledge his courage while not excusing his cruelty, and to recognise that even the most famous revolutionaries are products of their time, shaped by the conflicts and contradictions they sought to transcend.

His legacy remains unresolved because the questions he embodied remain unresolved: how to address profound social inequality, whether revolutionary violence can be justified in pursuit of social justice, and what individuals owe to those suffering oppression. These questions ensure that Che Guevara will continue to provoke debate and reflection for generations to come.

Leave a Reply