In April 1961, a small, heavily armed force of Cuban exiles stormed a remote stretch of Cuba’s southern coastline, expecting to spark a nationwide uprising that would topple revolutionary leader Fidel Castro. Instead, within three days, the invaders were surrounded, captured, or killed. The operation — planned, funded, and directed by the US Central Intelligence Agency — collapsed into one of the most humiliating foreign-policy disasters in modern American history.

The Bay of Pigs invasion didn’t just fail militarily. It reshaped Cold War politics, strengthened Castro’s rule, pushed Cuba closer to the Soviet Union, and set the stage for the nuclear brinkmanship of the Cuban Missile Crisis the following year. More than six decades later, it remains a case study in intelligence failure, political miscalculation, and the dangers of believing your own propaganda.

Revolution, fear, and the making of an enemy

When Fidel Castro seized power in Cuba in 1959, overthrowing dictator Fulgencio Batista, many Cubans initially celebrated the revolution. But Washington quickly grew alarmed. Castro nationalised American-owned businesses, redistributed land, and began aligning himself with socialist policies and Soviet support.

In the Cold War mindset of the late 1950s, a communist government just 90 miles from Florida was unacceptable to US policymakers. The Eisenhower administration authorised the CIA to organise Cuban exiles — many of them wealthy anti-Castro refugees, former soldiers, and political opponents — into a paramilitary force that could invade Cuba and remove Castro from power.

The plan was simple in theory: land an exile army, seize territory, proclaim a provisional government, and trigger a mass anti-Castro uprising. The US would deny direct involvement, presenting the invasion as an internal Cuban revolt.

But from the beginning, the operation rested on dangerously optimistic assumptions.

Brigade 2506: America’s secret army

The CIA recruited roughly 1,400 Cuban exiles into what became known as Brigade 2506. They were trained in Guatemala and Nicaragua, supplied with American weapons, and prepared for an amphibious assault.

CIA planners believed Castro’s rule was fragile and unpopular. Intelligence reports suggested that once the invasion began, Cuban civilians and elements of the military would defect and join the rebels.

That assumption would prove catastrophically wrong.

In reality, Castro’s government had strong support among workers, peasants, and nationalist Cubans who viewed the revolution as liberation from corruption and foreign control. Far from triggering revolt, the invasion would instead ignite patriotic resistance.

Kennedy inherits a covert war

By the time John F. Kennedy entered the White House in January 1961, the invasion plan was already well underway. Cancelling it risked appearing weak on communism; approving it carried enormous risks.

Kennedy authorised the operation but imposed strict limits designed to preserve plausible deniability. Most crucially, he reduced planned US air support, fearing that overt American involvement would expose the invasion as a US attack.

This decision would become one of the most debated elements of the entire episode.

Without sufficient air strikes, Castro’s small but effective air force survived, and it would soon dominate the battlefield.

The landing at the Bay of Pigs

Before dawn on 17 April 1961, Brigade 2506 landed at Playa Girón and Playa Larga on Cuba’s swampy southern coast, an area known as the Bay of Pigs.

Almost immediately, things went wrong.

Local resistance was stronger than expected. The swampy terrain limited movement and supply lines. Cuban government forces mobilised far faster than CIA planners predicted. Castro himself rushed to the front to direct operations.

Most devastatingly, Cuban aircraft attacked the invasion fleet, sinking supply ships and destroying vital ammunition and communications.

The exiles found themselves isolated, outnumbered, and trapped.

No popular uprising came. No mass defections occurred. Instead, thousands of Cuban militia and soldiers closed in.

Within 72 hours, the invasion was over.

Global embarrassment

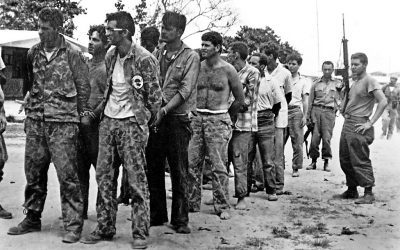

More than 100 invaders were killed. Around 1,200 were captured and paraded as proof of American aggression. The spectacle handed Castro a massive propaganda victory.

For the United States, the political damage was immediate and severe. The world now knew Washington had backed the invasion. America’s attempt at plausible deniability collapsed almost instantly.

President Kennedy publicly accepted responsibility, calling it a hard lesson in the limits of covert intervention.

The captured exiles were eventually released in 1962 in exchange for $53 million worth of food and medical supplies, an arrangement negotiated privately with Castro.

Why the plan failed

The disaster at the Bay of Pigs was not the result of a single mistake, but of a chain of misjudgments that began long before the first exile boat touched Cuban sand. Inside the CIA and the corridors of Washington, planners had built the entire operation on a dangerously flawed picture of Cuba itself. Reports suggested Fidel Castro’s rule was fragile, unpopular, and ready to collapse at the first serious challenge. In reality, his government had far deeper support than American intelligence believed. Instead of sparking rebellion, the invasion triggered a wave of national mobilisation, as thousands of Cuban soldiers and civilian militia rallied to defend the revolution.

At the same time, the political need for secrecy slowly strangled the military plan. President Kennedy wanted the operation to succeed — but he also wanted the United States’ role hidden from the world. To preserve that deniability, crucial air strikes were scaled back, leaving Castro’s air force intact. When the invasion began, those surviving Cuban aircraft quickly attacked the exile ships, destroyed supplies, and cut communications. What had been designed as a coordinated military assault became, almost instantly, a stranded force fighting without the support it had been promised.

Behind the scenes, another problem had already taken hold: few people inside the administration were willing to stop the momentum of the plan. Doubts existed, but they were muted. Officials reassured one another that the Cuban people would rise up, that the landing force would gain ground, that events would somehow turn in their favour. In the closed environment of Cold War decision-making, confidence replaced caution, and worst-case scenarios were quietly pushed aside.

Perhaps the greatest misunderstanding, however, was not military but cultural. American planners imagined the exiles would be welcomed as liberators returning to free their homeland. But for many inside Cuba, the sight of an invasion force trained and armed by the United States did not signal liberation — it signalled foreign interference. Whatever grievances some Cubans had with Castro, the invasion transformed the conflict into a nationalist struggle. Instead of collapsing, the regime found itself strengthened by the very attack meant to destroy it.

In the end, the Bay of Pigs failed because the planners misunderstood the country they were trying to change, restricted the very military force they relied upon, convinced themselves success was inevitable, and underestimated the power of national identity in the face of foreign intervention.

From disaster to nuclear crisis

Ironically, the invasion strengthened the very government it aimed to destroy.

Castro used the attack to justify tightening internal security, imprisoning opponents, and formally declaring Cuba a socialist state aligned with the Soviet Union.

For Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, the failed invasion confirmed that the United States intended to overthrow Castro by force if possible. This perception helped drive the Soviet decision to secretly install nuclear missiles in Cuba in 1962 — triggering the Cuban Missile Crisis, the closest the world has ever come to nuclear war.

In that sense, the Bay of Pigs was not just a failed invasion. It was a turning point that escalated Cold War tensions to their most dangerous peak.

A permanent lesson in covert war

Today, the Bay of Pigs invasion remains a textbook example studied in military academies, intelligence agencies, and political science courses.

It demonstrates how:

- intelligence agencies can become trapped in confirmation bias

- political leaders can inherit flawed plans that feel too advanced to stop

- covert operations can spiral into public catastrophes

- nationalist sentiment often outweighs external expectations

For Cuba, the invasion became a foundational myth of resistance against American imperialism. For the United States, it became a cautionary tale about intervention, secrecy, and the limits of regime-change strategies.

And for the world, it stands as a reminder that sometimes history’s biggest turning points happen not when plans succeed, but when they collapse spectacularly.

Leave a Reply