In the blood-soaked early decades of Spanish conquest in the Americas, one man’s voice rang out against the violence with a fury that would echo across centuries. Bartolomé de las Casas, Dominican friar, former conquistador, and arguably history’s first human rights activist, spent fifty years battling the very empire he once served, demanding that Spain recognise the humanity of indigenous peoples it was systematically destroying.

His legacy remains paradoxical and contested: a prophet of justice who nevertheless participated in the colonial project, a defender of indigenous rights whose writings inadvertently fueled anti-Spanish propaganda, and a radical whose arguments helped shape modern concepts of human rights while emerging from deeply medieval Catholic thought.

From conqueror to conscience

Born in Seville in 1484, Las Casas arrived in Hispaniola in 1502 as part of the Spanish colonial enterprise. Like other settlers, he participated in the encomienda system, which granted colonists control over indigenous labour in exchange for their “protection” and Christian instruction, a system that in practice meant brutal exploitation and enslavement.

For years, Las Casas saw nothing wrong with this arrangement. He became a priest in 1510, the first to be ordained in the Americas, while continuing to benefit from indigenous labour on his estates in Cuba. But in 1514, while preparing a sermon, he encountered a passage from the Book of Ecclesiasticus: “The bread of the needy is their life: he that defraudeth him thereof is a man of blood.”

The words shattered his worldview. At age thirty, Las Casas experienced what he would later describe as a conversion. He renounced his estates, freed the indigenous people under his control, and began a lifelong campaign against Spanish colonial practices that would make him one of the most controversial figures in the empire.

A prophet in the court

Las Casas understood that moral arguments alone would not move an empire. He became a master of political manoeuvring, making repeated journeys across the Atlantic to lobby the Spanish court, producing detailed legal briefs, and engaging in high-stakes theological debates.

His most famous work, A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies (1552), catalogued atrocities committed by Spanish colonists with searing, often graphic detail. He described indigenous populations being worked to death, babies torn from mothers’ arms and dashed against rocks, and systematic torture employed to extract gold. The work was deliberately inflammatory, written to shock the conscience of Prince Philip, the future king.

Critics then and now have accused Las Casas of exaggeration, and indeed, his estimated death tolls, claiming that Spanish actions killed millions, were likely inflated. Yet modern demographic research has confirmed the catastrophic population collapse he witnessed: diseases, warfare, forced labour, and disrupted food production reduced indigenous populations by an estimated 90 per cent within a century of contact.

The Short Account achieved its immediate purpose by contributing to the passage of the New Laws in 1542, which, in theory, ended indigenous slavery and restricted the encomienda system. But it also became a weapon in European power politics. Dutch and English Protestants, eager to discredit Catholic Spain, translated and republished Las Casas’s work widely, using it to construct the “Black Legend”, an exaggerated portrayal of Spanish uniquely cruel colonialism that conveniently overlooked their own imperial brutalities.

The Valladolid debate

The climax of Las Casas’s public career came in 1550 at Valladolid, where he engaged in a formal debate with the philosopher Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda before a council of theologians and lawyers. The question at stake: Were Spain’s wars against indigenous peoples justified?

Sepúlveda, drawing on Aristotle, argued that indigenous peoples were “natural slaves”, intellectually and morally inferior beings who benefited from Spanish domination. Their practices of human sacrifice and supposed cannibalism, he contended, proved their barbarism and justified conquest to end such evils.

Las Casas spent five days reading from a 550-page manuscript, systematically dismantling Sepúlveda’s arguments. Indigenous peoples, he insisted, were fully rational beings capable of self-governance and Christian faith. Their cultures, while different from European ones, showed sophistication in governance, arts, and architecture. Human sacrifice, though abhorrent, did not justify total war any more than European religious violence justified the conquest of European kingdoms. Conversion must be achieved through persuasion, not force.

The debate ended inconclusively, and the council never issued a definitive verdict. But Las Casas had forced the Spanish Empire into an unprecedented public reckoning with the morality of its own conquest, a self-examination almost unique among colonial powers.

The complicated legacy

Las Casas’s arguments planted seeds that would grow into modern human rights discourse. His insistence on universal human dignity, the illegitimacy of conquest, and the right of peoples to self-determination anticipated Enlightenment philosophy by two centuries. Yet his thought remained rooted in medieval Catholicism rather than in secular humanism. For Las Casas, indigenous rights derived from their status as potential Christians and children of God, not from any notion of secular equality.

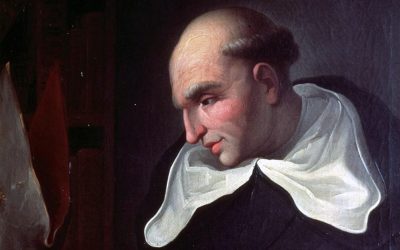

Hispalois, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

His legacy also bears a troubling stain. In his early advocacy, Las Casas briefly suggested that importing African slaves might spare indigenous populations from forced labour—a proposal he later recanted and condemned, but which has linked his name to the growth of the Atlantic slave trade. Modern scholars debate the extent of his responsibility, but the episode reveals the limitations of even the most radical moral vision when operating within fundamentally unjust systems.

Indigenous communities and scholars today hold varied views of Las Casas. Some honour him as a crucial ally who used his privilege to fight for justice. Others see him as a paternalistic figure who, despite good intentions, never questioned Spanish sovereignty itself and envisioned indigenous peoples primarily as subjects for conversion rather than as peoples with the right to preserve their own beliefs and ways of life.

Relevance in our time

In an era grappling with the legacies of colonialism, Las Casas’s life poses uncomfortable questions. Can one work meaningfully for justice from within oppressive systems? How do we evaluate historical figures who advanced moral understanding while remaining limited by their era’s blind spots? What obligations do nations bear for historical injustices?

Las Casas died in 1566 at age ninety-two, still writing, still advocating. He never saw the end of the encomienda system or the restoration of indigenous sovereignty. Spain continued its colonial project for centuries more. Yet his arguments survived, cited by later advocates for abolition, decolonisation, and human rights.

The friar who fought an empire didn’t win in any conventional sense. But he established that fighting itself as a moral obligation, the duty to speak against injustice even when the powerful seem invincible, to insist on the humanity of the dehumanised, and to imagine systems more just than those that exist. In that sense, his struggle continues wherever conscience confronts power.

Leave a Reply